Bloc Party - A Weekend In The City

A friend told me at the start of this year that bands were going for a bombastic, 80s, Echo & The Bunnymen type sound, using this as an example. He was absolutely right, as every one of these 20 records are big, loud, a little pretentious, and warm. Bloc Party's sophomore is a little harder edged than their debut, but it catches on just as quick. If Silent Alarm was Hammer Studios, Weekend is Tigon; with songs about Witches & Religion, the metaphor works doubly. While Weekend reaches much higher volume than Silent Alarm, it also has their first out-and-out pop tune in I Still Remember, which is needless to say a little lazier than the rest of the CD, but their new found fondness for synthesized sound works twice as hard to pick up the slack.

The New Pornographers - Challengers

Is that all? Challengers went by too quickly for my liking. It's the best record the group has ever done and they knew enough not to let it hang around long enough to disinterest listeners, a mistake they've made with their past three records. This time, pop bliss in 12 songs. Unexpected arrangements and some really interesting combinations of A.C. Newman's normal glamourous retro tunes and Dan Bejar's slow burners that make this record so fascinating. And just as you think it's time for the record to wear out it's welcome, it's finished and made you want more. They've excised all the flab and left in nothing but good things, and if the B-sides are any indication, they had plenty more in them.

Feist - The Reminder

/feist-reminder.jpg)

Yeah, ok, whatever. I really think in a year's time it'll be difficult for me to recall a time when I actually respected Feist. It seems only yesterday I was silently bragging about having discovered her. All the things that most of her critics have pointed out about her are more true than ever before on The Reminder - too put-on, faux-jazzy and zealous to invite real admiration. The good things don't exactly outweigh the poor show of character she's been up to (Ipod commercial? You must be joking. At least Rogue Wave needed money for an operation.) Those aforementioned good things happen to be the first half of the album. I'm Sorry is as simple and ageless as a Shakespeare sonnet and My Moon My Man is really a gem (I'd drive to the ends of the earth for that piano sound.)

Múm - Go Go Smear The Poison Ivy

Yes, even Múm has decided to augment their sound and their band and it turned out to be an incredibly smart move. Go Go is their most pop-driven record (in that now one can say they have one that sounds like a pop record) and it may have to do with the fact that they've now got seven members pulling (and strumming) the strings. Still weird? Absolutely. Still filled with blips and scratches? Definitely! still meandering and Icelandic? Well...not so much. Direction has taken something of the mystique from this band, as has it's use of English language lyrics, but, it proves that they're trying to hang around longer than the Valtýsdóttirs, their recently departed founders. I recognize that Múm is Múm in name only, the spirit is still there, they just need to stick it out.

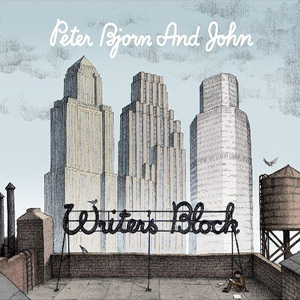

Peter Bjorn & John - Writer's Block

Purists will tell me that this came out in 2006 and they're right, but I didn't get my hands on a US copy until early this year, so I'm going to give them the benefit of a delayed release. Writer's Block is as simple as pop music has ever gotten and ten times as sweet as it normally gets. Peter Moren's voice begs for love to come true and his guitar drips out after it. The Object Of My Affections, Paris 2004, Roll The Credits, Start To Melt are all pitch-perfect pop tunes, and their extended lengths really help them stay in the brain.

Handsome Furs - Plague Park

I wish that I'd been the first to compare this to early Cure, but Britt Daniel from Spoon did it first. Mood aside, Handsome Furs' debut is minimalist and seething, swaggering almost as drunkenly as Dan Boeckner's Wolf Parade co-conspriator Spencer Krug's effort this year (more on this later). His guitar and lyrics let the world know exactly what it is he brings to Wolf Parade, and his contributions are evidently invaluable. He and his bride Alexei Perry combine programmed drums, a touch of synth and Boeckner's unmistakable tones to become something akin to Canada's White Stripes.

Yeah Yeah Yeahs - Is Is

Show Your Bones may have been the biggest letdown of 2006. Karen O and company decided to make a cock rock album and boy did it make me furious. How did they go about redeeming themselves? Making a killer EP with five songs crossing Siouxsie & The Banshees, Early Pretenders, Depeche Mode and all the glam-goth you can find. Karen O is up to her old tricks again and Nick Zinner has found an uglier guitar tone than Jack White, even, adding synth (like everyone else in the game) to set the scene and then stomping about with his recovered sleaze. This is a band at the top of it's game. Why is it so low on the list? Cause I want more dammit!

Animal Collective - Strawberry Jam

One of these days I'm going to have recommend my friend Meghan O'Donnell for a job discovering musical acts. Icy Demons, Architecture in Helsinki, Modest Mouse, all of them blew up months after she's explained everything good about them to me before music critics could pretend they thought of it first. Animal Collective is one such band. Meg knew that they were unlike anyone else, and here they've done what Meg knew they were capable of: the best and brightest music in their career, spun in a way unlike any other band in the business. Shouting, electronics, poly-rhythms, all present and accounted for and it's beautiful.

Broken Social Scene Presents Kevin Drew - Spirit If...

Granted this is more Shoegazer than Post-rock, but what kind of indie rock hound would I be to discount any Broken Social Scene related output in a year-end summation. I could do without all the DInosaur Jr. that makes its way onto Drew's record, but he's been star-struck ever since the Verizon festival and I suppose if I ever met Kevin Drew, i'd sure as shit make an album that sounded like BSS. What he does here is augment the BSS sound by making it full and melodious in ways the band hasn't been able to yet. The magic of Broken Social Scene is all the influences making a record that works in spite of itself. With Drew at the helm completely, it's one long experiment in pop sounds rising from static, and with help from Do Make Say Think members Charles Spearin and Ohad Benchetrit doing their share, the record works 99% of the time.

LCD Soundsystem - Sound Of Silver

The reason I don't put this higher on my list is because James Murphy seems to have saved all the high energy for their live shows and left his record a little wanting of that crazy-guy shtick he's gotten down to a science. It's kooky alright, but it stays grounded, which I wasn't expecting after his debut, which gave enough evidence that he was going to go all out next time. What does work here is the return to the routes of dance music, the old percussion sounds, the tremendous use of ancient synth, Murphy's signature falsetto, the picked bass, like the bastard son of Marshall Grant's fingers. These guys are tight, but they need some volume and a little more fight next time around. I know they've got it in them because the best song on the album (All My Friends) is the perfect example of letting their feet leave the ground. Instrument upon Instrument is added and Murphy screams and screams in vein about how he will never be young again, but he doesn't seem to realize he's creating a lasting testament to his many years with this song.

The Most Serene Republic - Populations

Just as I was sure I'd found the best Canadian collective album in Spirit If... This found it's way to my ears. It doesn't quite have the personality Broken Social Scene does, but they use static and all 7 of its members to the greatest of efficiency. The melodies and songs are noticeably different from their peers (at least to the disciplined ear) and sound alternately cold and distant at the right moments. The sound is varied and endlessly intriguing. Listening to the songs meld together is something that makes every scene much more pleasant.

Do Make Say Think - You, You're A History In Rust

.jpg)

Just how much do I love Canadians. Well, 9/20 of the albums here were made by them and probably aren't nearly as good as I make them out to be. Do Make Say Think really are as good as all this however. Before History, they'd made records I enjoy, but none have been so acerbically ingenious as this one. Their instrumental compositions range from boisterous post-rock to stripped down rovers and each stop is as unique and lovable as the next. These boys know have the feel of a band that know each other like they do every inch of their instruments. They've honed their craft into something dangerously self-aware and have put their contemporaries in a tough spot. How can Silver Mt. Zion or Explosions in the Sky possibly keep up with a band that keeps evolving in new directions?

Rogue Wave - Asleep At Heaven's Gate

Descended Like Vultures, Rogue Wave's second CD was really beautiful and was for the most part the work of principle songwriter Zach Rogue. Asleep is another matter entirely. How does a band prove they are more than one man's songs? They get loud. The first song, Harmonium is a pretty stellar example of full-band Rogue Wave at it's best. Drums like the pistons of a train, guitar that shimmers and screams in turn, bass that fits around the whole mess like a pair of velvet gloves, endless Piano guiding the song along. Critics hate this record which has led me to call this their Porcupine, a record brimming with new sounds and directions that will entertain for years to come but will never be given the credit it deserves.

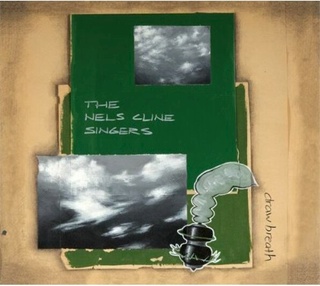

The Nels Cline Singers - Draw Breath

Nels Cline picked something up playing with Thurston Moore and Wilco all these years. Namely, how to make the most ballsy Jazz records in 30 years. I'd say he's the best guitar player in the world but I've never witnessed a duel between him and Omar Rodriguez-Lopez, one that I'm sure would end in fire and destruction should it ever be undertaken. This is a record that shifts between gorgeous twelve-string compositions accompanied by Contrabass and perfect percussion, to rockers driven by Cline's athletic fingering, to the all-out chaos he's made a name for himself with. This is a record that starts and ends on notes of lightness and sensitivity, but the middle is one of destruction, noise and brilliance. Which works better? I'll let you decide.

Dungen - Tio Bitar

As testament to this album's staying power, I think i've only listened to it once or twice all the way through, but I'll put it next to any rock album this year with confidence it'll psych them all into oblivion. The Swede's know how to rock out and this time they do a little more as a full band than just Gustav Ejstes pet project. Of course, Ejstses still does the lion's share of the work, but they sound much tighter here and the irony is that they are actually louder and rambunctious than ever before.

Sunset Rubdown - Random Spirit Lover

Spencer Krug is unlike any other songwriter in his game. Random Spirit Lover is like the score to a movie that was too bizarre and expensive to have ever been made - one with pirates, jungle cats, swashbuckling and the end of the world. His songs change as many as three times before the finish and make use of Jordan Robson-Cramer's guitar, the technique and sound of which i can only liken to some kind of serpent made of fire, not a bad description of Sunset Rubdown, come to think of it. Krug's endearing screams and keyboard-driven song-writing would make a decent foundation for any band, but as he's found a band that knows how to turn strange songs into untouchable genius.

Iron & Wine - The Shepherd's Dog

If anyone's looking for the definition of maturity, listen to The Sea & The Rhythm and then The Shepherd's Dog. Sam Beam isn't as depressed as he sounds. We all knew he could write the best songs one man can write, but, did anyone expect him to keep the magic with a full band? I was a little nervous when I heard Boy With A Coin, but he put all those worries to bed with Pagan Angel & The Borrowed Car, a song that makes use of every instrument present in as unpretentious a way as possible. I give Sam Beam permission to jump genres as he pleases as he's gone from one kind of bluesman to another with near-perfect results.

Apostle Of Hustle - The National Anthem Of Nowhere

Andrew Whiteman is probably the most underrated musician in Canada. No one has ever mentioned his virtuosic guitar playing as one of the gears that turns the Broken Social Machine or his fondness for Latin arrangements or his remarkable sense of composition. Whiteman's solo project has been all but ignored this year and it's a crime, as it's the big guitar record i've been waiting for. Whiteman and bassist Julian Brown trade monumental riffs over the icy fire of each song; they somehow recall both Summer and high Autumn. The music moves about like the body of a dancer and is equally as elegant and unpredictable.

Sondre Lerche - Phantom Punch

Sondre Lerche is brilliant; this record goes from Jazz to rock effortlessly and he did it a matter of months after his last record, which was one of complex arrangements and playing. How does he follow up his tribute to Elvis Costello, Burt Baccarach and Cole Porter? He pays tribute to Gang Of Four. This record rocks hard whenver it wants to, but never loses Lerche's nice-guy humane touch, never leaves the ground or reverts to screaming. No, the only screaming done here is by Kato Ådland's guitar and it sounds like it's been dying to break out these licks. Sondre Lerche is an entertainer on the level of his hero Elvis Costello and can balance hard and soft better than Elvis ever learned how to. Absolutely Sensational.

Arcade Fire - Neon Bible

I don't know if they're afraid of sounding predictable or if they are just unenlightened, but Rolling Stone, Spin, Paste and every other music rag has FAILED to notice what this is. Neon Bible is the greatest album made during my lifetime and when men twice my age concur, I can't help but reinforce this point. This is the album that every indie band in the world has been trying to make, but has so far fallen short of. Their music is as organic as possible; the song-writing team are lovers, their band can and frequently do play anything, their talents are all utilized perfectly. On Funeral, it was clear that some songs were weaker than others, however, here, there is no weak spot. It is an unrelentingly powerful work that has the same fire and passion that Mozart, Rachmaninov & Brahms work all brimmed with, except their work doesn't take so long to come to the point. This is honest music that will be as good at the end of the world as it is now. If you claim not to like this album or claim that someone has written a better record this year, you are either very foolish, a republican or very possibly the devil himself. This is music, and it may never get better than these 11 songs in a row. I've tried in vein to pick a favorite, but everyone is as glorious as the next. I have to believe it's some kind of ruse or dare when magazines choose The Boxer by The National or New Wave by Against Me as the best record this year. There is no question or competition. When Funeral, the Arcade Fire's debut came out at the tail end of 2004, it took only one listen for it to be the best record of that year. There second record was more or less destined to be the most powerful, divine work of modern music and the planets aligned and the Arcade Fire gave birth to the most urgent, criminally beautiful album they could have given. Why am I so insistent that this is the best record of all time? Someone's got to be and if the media is too fucking obtuse not to notice what this is, an unrivaled masterwork, than at least I won't be accused of rehashing old ideas. I've seen them live twice now and I've never felt more like I was part of some kind of religious experience.