Hello. I'm Scout and I'm a completist. This has gotten me into trouble over the years. I mean how often do people really mean "author of one great film" when they say Great Director? I could have been spared The Brothers Grimm, The Raccoon Princess, Bitter Moon and so much more if only I hadn't been endlessly compelled to delve further into the recesses of some of my favourite director's minds. I could have sat out the fucking extended cut of 1900, but no! Five and a half hours of my life....gone! I also could have been spared some of the least interesting/wrongly bolstered horror films of the 70s and 80s if only I didn't feel compelled to watch everything that was banned by the British Board of Film Classifications in the 80s under a summary ban that would later be dubbed the video nasties scare. In an effort to fight perceived obscenity, the board went to video stores all over the country confiscating video cassettes and slapping hefty fines on vendors. Now, while it's certainly interesting to examine what films were banned and why, the reasons all boil down to the simple fact that the BBFC were full of shit. Censorship in any form is regressive and counter-productive and the video nasties were no exception. By banning these films for poorly executed scenes of graphic violence (Bloody Moon) mixed with bizarre scenes of awkward sex and drug use (The Witch Who Came From The Sea) all they were ensuring was that kids would be impressed by the "BANNED IN 31 COUNTRIES" sticker on the box when it eventually found its way into the public's hands. The director of public prosecutions didn't watch half of these films (hence the now semi-famous story of the police snagging a shipment of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas believing it was pornography - a mistake also made by Doctor Venture) and before the likes of Mary Whitehouse were sent packing, the video nasties would start eating themselves. when rumours circulated that when the ad campaign for Cannibal Holocaust backfired, the British distributors called in a raid on their own movie so they could regenerate publicity for the film by having it banned. Controversy could sell the unsellable; it could certainly sell shit like Frozen Scream and Don't Go Near The Park. Furthermore, sometimes all you needed was the promise or even the hint of controversy to tempt viewers. Today we'll see how the influence of even the lowest trash can be pervasive if the promise of scandal is going to put asses in seats. Specifically, let's just look at the influence The Last House On The Left had on the exploitation circuit in the late 70s when it made it's way to Italy.

Night Train Murders

by Aldo Lado

We see two parties making their way to the same train out of Berlin. The first is a pair of girls leaving for christmas break. Lisa is the more prudish of the two and by far the cuter of them (Laura D'Angelo made precious few films and this is the only one available in the states as far as I can tell) and Margaret is a little more adventurous. The other pair are thieves who can't quite decide if they're greasers, hippies or, as we'll find out, murderous gremlins. They are also two of the ugliest men in a country that produces some of the ugliest men on the planet at a time when you couldn't swing a dead cat without hitting an ugly guy. Flavio Bucci and Gianfranco De Grassi are fucking hideous, which is really a feat on Aldo Lado's part because they've looked presentable in other films. Flavio Bucci was even half-cute in Suspiria but here as Blackie, I can't think of a less appealing human face. Anyway, they soon find themselves sharing a compartment with Lady on the Train (which is all the name she gets), an aristocrat who talks in half-formed platitudes. This is one of those movies where people go ahead and just announce the theme of the movie at the first opportunity so they can get to the stabbing and raping sooner. It's the screenwriter's way of clapping his hands and saying "Well that takes care of that!" Anyway Lady on the Train, or Lott, as I'll call her from now on, takes Flavio into the bathroom for a sex scene that I wanna say was aiming at slapstick comedy, but who can say?There are far more zooms than I thought possible in a train bathroom, so kudos for that, but jesus is this weird.

We see two parties making their way to the same train out of Berlin. The first is a pair of girls leaving for christmas break. Lisa is the more prudish of the two and by far the cuter of them (Laura D'Angelo made precious few films and this is the only one available in the states as far as I can tell) and Margaret is a little more adventurous. The other pair are thieves who can't quite decide if they're greasers, hippies or, as we'll find out, murderous gremlins. They are also two of the ugliest men in a country that produces some of the ugliest men on the planet at a time when you couldn't swing a dead cat without hitting an ugly guy. Flavio Bucci and Gianfranco De Grassi are fucking hideous, which is really a feat on Aldo Lado's part because they've looked presentable in other films. Flavio Bucci was even half-cute in Suspiria but here as Blackie, I can't think of a less appealing human face. Anyway, they soon find themselves sharing a compartment with Lady on the Train (which is all the name she gets), an aristocrat who talks in half-formed platitudes. This is one of those movies where people go ahead and just announce the theme of the movie at the first opportunity so they can get to the stabbing and raping sooner. It's the screenwriter's way of clapping his hands and saying "Well that takes care of that!" Anyway Lady on the Train, or Lott, as I'll call her from now on, takes Flavio into the bathroom for a sex scene that I wanna say was aiming at slapstick comedy, but who can say?There are far more zooms than I thought possible in a train bathroom, so kudos for that, but jesus is this weird.Anyway, so the train has to make a stop so all of our characters get off and transfer to a mostly empty train. This is where the personality development part of the movie not only stops, but gets erased. So Lott convinces Blackie and Curly (those are the totally awesome names given to the two guys) that what would be a gas is raping and stabbing both the girls, Weasel and Krug style. Then some dude shows up to spy on them and they make him take part in the gang rape, too. Then through circumstances far too stupid to go into, Blackie, Curly and Lott wind up at Lisa's parents' house and then through even more preposterous circumstances they figure out that their three house guests killed the two girls. And, I'll give Aldo Lado this, he skimps on the revenge aspect of this rape-revenge film just like Last House on the Left. Though at least Wes Craven went a little off the rails in that department; Lado just gets it over with, which is really fucking aggravating and unfair, I gotta say. The problem is that Lado assumed that because he has characters stop the action of the movie to discuss crime like they were aliens who'd just learned what happens in earth prisons he could show you the worst shit he could think of and it would all come out in the wash. The biggest tell is that when talking about the depiction of the rich in the movie in interviews, Lado makes constant reference to the middle class, but what he means is the upper class. At no point do we meet anyone who could be described as middle class and if there were someone more upper class in Italy than the Stradis and the neighbors who attend their lavish christmas party, than Lado really should have aimed for them because these people seem pretty Upper Class to me. And furthermore the lower class are presented as evil fucktards, even if the rich are pulling the strings. I'm sorry, that's not intelligent commentary, that's a blanket excuse to be an ignorant asshole. So, if Lado couldn't tell the difference, or didn't care, then he's full of shit and the idea that we should be taking cues from this dickbag is hysterical. Even funnier is that our auteur invited the whole of the Italian artistic community to the premiere and watched in reverent silence as the likes of Bernardo Bertolucci and Lina Wertmuller walked out in disgust. Lado had a big enough head on his shoulders to get great coverage of the train and more or less seamlessly mix studio shooting with locations and yet fails to make a case for his integrity and morals and thought that any response to his trashy ass movie was a good response.

The way that Blackie and Curly finally kill Lisa Stradi is by stabbing her between her legs. If any image ever defined the ruthlessness of Italian Exploitation Cinema, it's this, in a first wave rip-off of one of the most hated/inappropriately respected films of the 70s. Blackie, Curly and Lott don't learn anything which tells me that Lado and his legion of screenwriters simply didn't get it. Tell me something, why for all the fucking screenwriters attached to every third rate giallo do they always play like braindead rip-offs of better movies? Seriously, when you can't one-up Last House on the Left, you're in fucking trouble. Even with lavish production values and a killer Ennio Morricone score (Lado hilariously tries to make believe that De Grassi is playing the movie's theme on his harmonica when the man clearly doesn't even know how the instrument works) Night Train Murders is nothing but a trip into the sick and irredeemable, something the Italians did very well. In fact, that's just one of the things that Late Night Trains (alternate title) and Hitch-Hike, our next movie, had in common, that they were trips into the sick and irredeemable. For instance they both had Ennio Morricone scores and they were both first-wave Last House rip-offs. Of course Hitch-Hike did Trains one better of actually getting David Hess, Krug from Last House, to basically reprise his role. This was as much a blessing as a curse. Surely anything with David Hess would immediately confuse a public hungry for controversy, but it also meant having David Hess in your movie. Hess is almost as bad as his co-stars speaking in their second or third language. And even though Pasquale Festa Campanile is a little better a director than Aldo Lado, he still can't make a movie that outdoes Last House in shock value.

The way that Blackie and Curly finally kill Lisa Stradi is by stabbing her between her legs. If any image ever defined the ruthlessness of Italian Exploitation Cinema, it's this, in a first wave rip-off of one of the most hated/inappropriately respected films of the 70s. Blackie, Curly and Lott don't learn anything which tells me that Lado and his legion of screenwriters simply didn't get it. Tell me something, why for all the fucking screenwriters attached to every third rate giallo do they always play like braindead rip-offs of better movies? Seriously, when you can't one-up Last House on the Left, you're in fucking trouble. Even with lavish production values and a killer Ennio Morricone score (Lado hilariously tries to make believe that De Grassi is playing the movie's theme on his harmonica when the man clearly doesn't even know how the instrument works) Night Train Murders is nothing but a trip into the sick and irredeemable, something the Italians did very well. In fact, that's just one of the things that Late Night Trains (alternate title) and Hitch-Hike, our next movie, had in common, that they were trips into the sick and irredeemable. For instance they both had Ennio Morricone scores and they were both first-wave Last House rip-offs. Of course Hitch-Hike did Trains one better of actually getting David Hess, Krug from Last House, to basically reprise his role. This was as much a blessing as a curse. Surely anything with David Hess would immediately confuse a public hungry for controversy, but it also meant having David Hess in your movie. Hess is almost as bad as his co-stars speaking in their second or third language. And even though Pasquale Festa Campanile is a little better a director than Aldo Lado, he still can't make a movie that outdoes Last House in shock value.Hitch-Hike

by Pasquale Festa Campanile

Walter and Eve Mancini are maybe the fussiest and most annoyingly unhappy couple on earth. Walter is a journalist on leave who obviously misses the excitement of chasing revolutionaries for interviews. They're making a roadtrip through Italy...sorry, California, specifically near Barstow. Though, seriously, come the fuck on. Anyway, they stop at a campsight and get good and drunk while hanging out with a group of hippies. Walter gets so drunk that he falls and breaks his arm while trying to berate Eve for one of the many things he hates about her. The next day they pick up Adam Konitz, a hitchhiker who flips out at the sound of the news being broadcast on the car radio. A robbery, you say? Just down the road, you say? Killer still at large, you say? He's in the backseat, you say? Yes, Konitz has double-crossed his partners and made off with the money and now Eve and Walter are his hostages for as long as he feels like fucking with them. Mostly what he does (and Walter and Eve are all too happy to join him) is fucking yap endlessly about whatever the hell pops into his addled brain. We hear his take on the police, on journalists, on crime, on his childhood. My favourite quote, on his life as a criminal: "My head! My Head in the sights of their high-powered carbines! YOU DIDN'T THINK I WOULD DO IT!!! I'm Smarter than you think! You're a phony! You've always been a phony! You always will be a phony!" I realize that doesn't make much sense out of context but it's literally the best part of the film so I thought I'd share it. If you could maybe find it on youtube, you could skip the movie and save yourself two hours.

Walter and Eve Mancini are maybe the fussiest and most annoyingly unhappy couple on earth. Walter is a journalist on leave who obviously misses the excitement of chasing revolutionaries for interviews. They're making a roadtrip through Italy...sorry, California, specifically near Barstow. Though, seriously, come the fuck on. Anyway, they stop at a campsight and get good and drunk while hanging out with a group of hippies. Walter gets so drunk that he falls and breaks his arm while trying to berate Eve for one of the many things he hates about her. The next day they pick up Adam Konitz, a hitchhiker who flips out at the sound of the news being broadcast on the car radio. A robbery, you say? Just down the road, you say? Killer still at large, you say? He's in the backseat, you say? Yes, Konitz has double-crossed his partners and made off with the money and now Eve and Walter are his hostages for as long as he feels like fucking with them. Mostly what he does (and Walter and Eve are all too happy to join him) is fucking yap endlessly about whatever the hell pops into his addled brain. We hear his take on the police, on journalists, on crime, on his childhood. My favourite quote, on his life as a criminal: "My head! My Head in the sights of their high-powered carbines! YOU DIDN'T THINK I WOULD DO IT!!! I'm Smarter than you think! You're a phony! You've always been a phony! You always will be a phony!" I realize that doesn't make much sense out of context but it's literally the best part of the film so I thought I'd share it. If you could maybe find it on youtube, you could skip the movie and save yourself two hours.Pacing, or more plainly boredom, is Hitch-Hike's biggest problem. Hitch-Hike couldn't be any more plainly a rip-off of Last House on the Left and even though it's an example of much more assured filmmaking, to be sure, but it's just interminable. What Hitch-Hike boils down to is a scenery chewing contest between David Hess and Franco Nero. Hess has his histrionic violent outbursts where he rages against things like our "Homosexual society" and that insane laughter on his side. Nero's got his accented world-weariness, which makes him sound like Andy Samberg from that one Digital Short where he's slept with everyone in Ryan Philippe's life, including himself. But really a terrible (over)acting competition can't sustain a movie so fucking long. Campanile manufactures a kind of dusty, hillbilly vibe what with the never-ending music and campfires almost like he was aiming at Deliverance and hit Toon Town instead. Honestly the film isn't terribly made, it's just pointless. Totally pointless. What the hell was the point of this movie other than to point out that, yes, David Hess characters enjoy sex and murder. But that's written into their DNA. Just look at him! It'd be a surprise if the man weren't a rape hungry psychopath. And yet, despite his being completely unable to act, the Italian exploitation machine wasn't done with him, but we'll come back to that. Let's take a quick detour to the US.

In 1972, Roger Watkins poured a lot of himself into a film he called at the time The Cuckoo Clocks of Hell which was a labour of love and ran an unsupportable 175 minutes. It was the story of a psychopath who recruits some low-life friends and decides to kill some people who produce porn films and stag reels. The revenge motive probably made more sense when the movie was still called The Cuckoo Clocks Of Hell or At The Hour of Our Death, another title Watkins tossed around. But in the world of drive-in budgeted movies with drive-in levels of gore and mayhem and especially something with as gross and depressing a moral as Watkins film possesses, At The Hour was never going to see the light of day in its original form. And such was the influence of Last House on the Left that At The Hour of Our Death was rebranded in its image. The Cinematic Releasing Corporation got ahold of it in '77 and shaved just about everything except for the skeleton of a plot and most of the gore. Watkins was livid and distanced himself from the whole mess and in fact didn't know the thing had been released until someone recognized him on the street as "the guy from that sick movie". There isn't much that The Last House On Dead End Street has in common with Last House On The Left except for the graphic violence and post-modernism. But, it's way better and somehow even more full of despair.

In 1972, Roger Watkins poured a lot of himself into a film he called at the time The Cuckoo Clocks of Hell which was a labour of love and ran an unsupportable 175 minutes. It was the story of a psychopath who recruits some low-life friends and decides to kill some people who produce porn films and stag reels. The revenge motive probably made more sense when the movie was still called The Cuckoo Clocks Of Hell or At The Hour of Our Death, another title Watkins tossed around. But in the world of drive-in budgeted movies with drive-in levels of gore and mayhem and especially something with as gross and depressing a moral as Watkins film possesses, At The Hour was never going to see the light of day in its original form. And such was the influence of Last House on the Left that At The Hour of Our Death was rebranded in its image. The Cinematic Releasing Corporation got ahold of it in '77 and shaved just about everything except for the skeleton of a plot and most of the gore. Watkins was livid and distanced himself from the whole mess and in fact didn't know the thing had been released until someone recognized him on the street as "the guy from that sick movie". There isn't much that The Last House On Dead End Street has in common with Last House On The Left except for the graphic violence and post-modernism. But, it's way better and somehow even more full of despair.The Last House On Dead End Street

by Roger Watkins

Terry Hawkins has left prison an angry, spiteful little man. But, as his endless inner monologue tells us, he's going to do something they won't see coming! That'll show 'em! Somehow! His solution, rent a room and with some shady connections, start shooting porn/snuff films. His connection spent time in an asylum for having sex with a calf while working for a slaughterhouse, so you know he's game. His movies start to gain a reputation which get around to the ears of Jim Palmer, noted porn film producer who's star has fallen. During one of the most heart-sinking sex parties in film history, Palmer shows his latest film to his benefactor who's not pleased. "You're showing me tenth rate porn while your wife is in the next room getting her ass whipped and you have the nerve to talk to me about reputation!" Palmer promises to get some new ideas and Hawkins might just be his answer. Their arrangement starts sleazily enough when Hawkins shows up at Palmer's house and finds his wife alone and before too long the two are in bed. Nancy, Mrs. Palmer, having seen Hawkins films, asks him how he makes it look so real? The simple answer is that it is real. Hawkins' films, you see, are a potent mix of sex and murder that sells very well (which really was the truth in the early 70s). The only difference between typical grindhouse fare/porn is that Hawkins and his crew are actually killing people. And before too long Palmer, his boss and his wife have fallen into Hawkins' clutches. Palmer needed new material for his films; who knew he'd wind up solving his own problem?

Terry Hawkins has left prison an angry, spiteful little man. But, as his endless inner monologue tells us, he's going to do something they won't see coming! That'll show 'em! Somehow! His solution, rent a room and with some shady connections, start shooting porn/snuff films. His connection spent time in an asylum for having sex with a calf while working for a slaughterhouse, so you know he's game. His movies start to gain a reputation which get around to the ears of Jim Palmer, noted porn film producer who's star has fallen. During one of the most heart-sinking sex parties in film history, Palmer shows his latest film to his benefactor who's not pleased. "You're showing me tenth rate porn while your wife is in the next room getting her ass whipped and you have the nerve to talk to me about reputation!" Palmer promises to get some new ideas and Hawkins might just be his answer. Their arrangement starts sleazily enough when Hawkins shows up at Palmer's house and finds his wife alone and before too long the two are in bed. Nancy, Mrs. Palmer, having seen Hawkins films, asks him how he makes it look so real? The simple answer is that it is real. Hawkins' films, you see, are a potent mix of sex and murder that sells very well (which really was the truth in the early 70s). The only difference between typical grindhouse fare/porn is that Hawkins and his crew are actually killing people. And before too long Palmer, his boss and his wife have fallen into Hawkins' clutches. Palmer needed new material for his films; who knew he'd wind up solving his own problem? It's easy to call The Last House on Dead End Street disjointed and confusing, but it's not Watkins fault. The 175 minute cut probably explained why there are a few voiceover tracks other than the hero's, or why Hawkins felt the need to kill Palmer's boss or why Hawkins had the urge to direct in the first place. What won't be explained is why the film is so unremittingly bleak. Dead End Street is dark. Courageously dark. Clockwork Orange with no charisma, dark. Charles Manson's the main character dark. There's a woman being whipped while in blackface for christ sakes! Can you believe that shit? Holy fucking christ! The film's boldness starts and ends with Hawkins. He is really a punch-in-the-gut as a main character. He looks like Bill Hader in Hot Rod and he's out of his goddamned mind. The last half hour of the movie is dedicated to the surprisingly realistic depiction of three people being tortured and maimed with power tools while Hawkins directs and films it all. It'd be dark enough without the gore being so convincing - I'm 99% sure they used animal parts in these scenes as Michael Cimino hadn't blown up enough horses for that to be banned from film sets yet. But, yeah, it really doesn't get much darker than this and the music lets us know that Watkins understood how fucking miserable a movie he was making and he wanted it to be even bleaker! The ending promises us that Hawkins was caught and he and his band were imprisoned but Watkins thought that ruined the whole film. He's not wrong in that it does take something away from the visceral snuff-feeling of the picture, but it also adds a kind of mysteriousness, almost like comic book villainy to the characters, which means that they stay with you.

It's easy to call The Last House on Dead End Street disjointed and confusing, but it's not Watkins fault. The 175 minute cut probably explained why there are a few voiceover tracks other than the hero's, or why Hawkins felt the need to kill Palmer's boss or why Hawkins had the urge to direct in the first place. What won't be explained is why the film is so unremittingly bleak. Dead End Street is dark. Courageously dark. Clockwork Orange with no charisma, dark. Charles Manson's the main character dark. There's a woman being whipped while in blackface for christ sakes! Can you believe that shit? Holy fucking christ! The film's boldness starts and ends with Hawkins. He is really a punch-in-the-gut as a main character. He looks like Bill Hader in Hot Rod and he's out of his goddamned mind. The last half hour of the movie is dedicated to the surprisingly realistic depiction of three people being tortured and maimed with power tools while Hawkins directs and films it all. It'd be dark enough without the gore being so convincing - I'm 99% sure they used animal parts in these scenes as Michael Cimino hadn't blown up enough horses for that to be banned from film sets yet. But, yeah, it really doesn't get much darker than this and the music lets us know that Watkins understood how fucking miserable a movie he was making and he wanted it to be even bleaker! The ending promises us that Hawkins was caught and he and his band were imprisoned but Watkins thought that ruined the whole film. He's not wrong in that it does take something away from the visceral snuff-feeling of the picture, but it also adds a kind of mysteriousness, almost like comic book villainy to the characters, which means that they stay with you. Last House on Dead End Street might not be the best thing hidden from the sun but it is a film that is as strong as its convictions. It's dark and clearly didn't have much of a budget but as one of the great 70s mind-of-a-fucking-nutjob movie it really does the job. And it does a lot else well, too. Take the weirdly intimate and awkward conversation Palmer has with his boss as he tries to explain how to sell the mediocre pornographic film he's made with his wife as the star. It's tremendously uncomfortable but Watkins doesn't flinch. The humanity of these sleazy fuckers is put nakedly on display and it's a definite mark in favour of Watkins and his uncompromising vision. In an era where directorial excess runs rampant it's tough to think about watching a three hour cut of Last House on Dead End Street but I'm significantly intrigued by his one directorial effort that if the option ever presented itself, the stupidly stubborn completist in me might just force the rest of me to watch it. That same idiot completist was also running the show when he decided I simply had to watch all of the fiction work of Franco Prosperi, the ghoul behind Goodbye, Uncle Tom and Africa Addio. After all, how truly awful could Last House on the Beach really be? There's no way it'd approach the monstrous reality of Goodbye, Uncle Tom or the sheer witless exploitation of the likes of Mondo Cane. And yet, what fucking moron watches Last House on the Beach when he knows how bad its director can be? Who's got two thumbs, four years of film school and nothing better to do with himself? This guy!!!!!

Last House on Dead End Street might not be the best thing hidden from the sun but it is a film that is as strong as its convictions. It's dark and clearly didn't have much of a budget but as one of the great 70s mind-of-a-fucking-nutjob movie it really does the job. And it does a lot else well, too. Take the weirdly intimate and awkward conversation Palmer has with his boss as he tries to explain how to sell the mediocre pornographic film he's made with his wife as the star. It's tremendously uncomfortable but Watkins doesn't flinch. The humanity of these sleazy fuckers is put nakedly on display and it's a definite mark in favour of Watkins and his uncompromising vision. In an era where directorial excess runs rampant it's tough to think about watching a three hour cut of Last House on Dead End Street but I'm significantly intrigued by his one directorial effort that if the option ever presented itself, the stupidly stubborn completist in me might just force the rest of me to watch it. That same idiot completist was also running the show when he decided I simply had to watch all of the fiction work of Franco Prosperi, the ghoul behind Goodbye, Uncle Tom and Africa Addio. After all, how truly awful could Last House on the Beach really be? There's no way it'd approach the monstrous reality of Goodbye, Uncle Tom or the sheer witless exploitation of the likes of Mondo Cane. And yet, what fucking moron watches Last House on the Beach when he knows how bad its director can be? Who's got two thumbs, four years of film school and nothing better to do with himself? This guy!!!!!The Last House On The Beach

by Franco Prosperi

Sister Cristina is in charge of chaperoning a group of aspiring actresses while they study for their exams. Three bank-robbers, blah fucking blah, we spend the whole movie watching three guys rape and torment six women and then about eight seconds on the revenge the ones still alive reap. The first thing to say is that Last House on the Beach is an even lousier movie than Last House on the Left in every respect. The only thing it doesn't have is 'comically' overblown racial stereotypes and banjo music. What it does have is a nude dance show on TV called "Program Babies," terrible continuity, a soundtrack that is on the radio as often as it's underneath the action of any given scene, a shit load of doing nothing by the pool, heterosexual men putting on make-up before gang raping a girl, and chase scenes where both parties seem to be just kinda jogging. It's lazy and seems completely unaware both of the horrid things its characters are doing and of how poor a job everyone involved was doing. Prosperi seemed to sense that he was working with a paltry budget and that his 'best' work was behind him because the phrase "phoning it in" just doesn't do justice to the series of yawns and half-nods that constitute his direction. Not even the usually sturdy Ray Lovelock turns in anything like decent work. He doesn't even have a beard to hide behind. In other words this is the blandest movie about rape I've ever seen. And make no mistake this is all about rape; hell, one of the characters is a nun! Everything's in place to make this the kind of thing Prosperi ousted himself from polite society with in the first place but for whatever reason he brought nothing of his shark-like intensity to the project. I mean on paper, and to a degree in practice, the film is truly tasteless and terrible, it's just that it is executed so lazily that to attack it hardly seems worth the energy. Prosperi had already been declawed by the industry that bred him. Last House on the Beach is a skeleton of a movie that can only offend people who've never seen anything of its type before and by now I've seen so much worse that it's instantly forgettable except when it's exceptionally silly, as when one of the rapists puts on the captive girls' make-up. I'd take issue with the fact that the women do away with their captors with brooms and rakes instead of the fucking guns they get hold of, but then that'd be playing Prosperi's game.

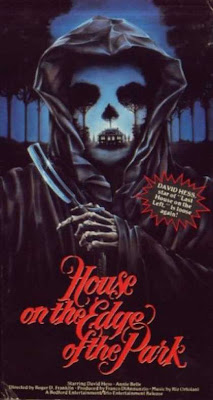

Sister Cristina is in charge of chaperoning a group of aspiring actresses while they study for their exams. Three bank-robbers, blah fucking blah, we spend the whole movie watching three guys rape and torment six women and then about eight seconds on the revenge the ones still alive reap. The first thing to say is that Last House on the Beach is an even lousier movie than Last House on the Left in every respect. The only thing it doesn't have is 'comically' overblown racial stereotypes and banjo music. What it does have is a nude dance show on TV called "Program Babies," terrible continuity, a soundtrack that is on the radio as often as it's underneath the action of any given scene, a shit load of doing nothing by the pool, heterosexual men putting on make-up before gang raping a girl, and chase scenes where both parties seem to be just kinda jogging. It's lazy and seems completely unaware both of the horrid things its characters are doing and of how poor a job everyone involved was doing. Prosperi seemed to sense that he was working with a paltry budget and that his 'best' work was behind him because the phrase "phoning it in" just doesn't do justice to the series of yawns and half-nods that constitute his direction. Not even the usually sturdy Ray Lovelock turns in anything like decent work. He doesn't even have a beard to hide behind. In other words this is the blandest movie about rape I've ever seen. And make no mistake this is all about rape; hell, one of the characters is a nun! Everything's in place to make this the kind of thing Prosperi ousted himself from polite society with in the first place but for whatever reason he brought nothing of his shark-like intensity to the project. I mean on paper, and to a degree in practice, the film is truly tasteless and terrible, it's just that it is executed so lazily that to attack it hardly seems worth the energy. Prosperi had already been declawed by the industry that bred him. Last House on the Beach is a skeleton of a movie that can only offend people who've never seen anything of its type before and by now I've seen so much worse that it's instantly forgettable except when it's exceptionally silly, as when one of the rapists puts on the captive girls' make-up. I'd take issue with the fact that the women do away with their captors with brooms and rakes instead of the fucking guns they get hold of, but then that'd be playing Prosperi's game. And yet it's not even true that there wasn't power in the subject matter. I had thought that if Prosperi couldn't manage to get me to cover my eyes anymore, maybe no one could. Then I saw House On The Edge Of The Park. I'd been reading about Ruggero Deodato's second-most infamous film since I'd discovered the world of online horror writing around 2004/2005ish, back when I was trying to fill the hours working at my grandfather's biotechnical firm. This film, they all claimed, had teeth. And to be honest I was almost among them. But I realized the only reason I was cringing so bad was that I was watching it with my dad, who, while certainly more liberal than most parents, hasn't been dulled to the inherent motherfuckery of Italian horror films like I have. If I'd watched House On The Edge Of The Park by my lonesome, it would just have been another exercise in pointless "and then this happened" cruelty to no ends because after ten years of rip-offs, Last House's goose has surely been left in the oven and forgotten. But I did see that to the uninitiated, House on the Edge of the Park does have the power to offend. I have to give Ruggero Deodato that if nothing else. Although, it's not like he ever had trouble offending people...

And yet it's not even true that there wasn't power in the subject matter. I had thought that if Prosperi couldn't manage to get me to cover my eyes anymore, maybe no one could. Then I saw House On The Edge Of The Park. I'd been reading about Ruggero Deodato's second-most infamous film since I'd discovered the world of online horror writing around 2004/2005ish, back when I was trying to fill the hours working at my grandfather's biotechnical firm. This film, they all claimed, had teeth. And to be honest I was almost among them. But I realized the only reason I was cringing so bad was that I was watching it with my dad, who, while certainly more liberal than most parents, hasn't been dulled to the inherent motherfuckery of Italian horror films like I have. If I'd watched House On The Edge Of The Park by my lonesome, it would just have been another exercise in pointless "and then this happened" cruelty to no ends because after ten years of rip-offs, Last House's goose has surely been left in the oven and forgotten. But I did see that to the uninitiated, House on the Edge of the Park does have the power to offend. I have to give Ruggero Deodato that if nothing else. Although, it's not like he ever had trouble offending people...House On The Edge Of The Park

by Ruggero Deodato

Alex (David Hess once again. Kill me!) is a lowlife mechanic who (randomly? habitually? who the fuck knows?) picks up a woman in a cab on the streets of New York, pulls over and then rapes and kills his passenger. An indeterminate amount of time passes and we join Alex once again. He works at a garage with his mentally handicapped friend Ricky. A couple of well-dressed assholes pulls up complaining of car trouble. The last thing Alex wants is to be waylaid by these two - Tom and Lisa are there names - but he changes his mind when he sees that Lisa is played by Joe D'Amato regular Annie Belle. Well, not only does he fix their car after drinking Lisa in, he also decides that it's in his and Ricky's best interest to head to the party the two well-dressed yuppies are late for. He also decides he needs to bring the razor he killed that poor girl from the prologue with him. Let's now pause to say that the scenes of their El Dorado cruising around Manhattan is the last great thing to admire in this movie. Giovanni Lombardi Radice is Ricky is a close second, definitely, but Deodato made great use of his one night of location shooting. Anyway, back to this fucking movie.

Alex (David Hess once again. Kill me!) is a lowlife mechanic who (randomly? habitually? who the fuck knows?) picks up a woman in a cab on the streets of New York, pulls over and then rapes and kills his passenger. An indeterminate amount of time passes and we join Alex once again. He works at a garage with his mentally handicapped friend Ricky. A couple of well-dressed assholes pulls up complaining of car trouble. The last thing Alex wants is to be waylaid by these two - Tom and Lisa are there names - but he changes his mind when he sees that Lisa is played by Joe D'Amato regular Annie Belle. Well, not only does he fix their car after drinking Lisa in, he also decides that it's in his and Ricky's best interest to head to the party the two well-dressed yuppies are late for. He also decides he needs to bring the razor he killed that poor girl from the prologue with him. Let's now pause to say that the scenes of their El Dorado cruising around Manhattan is the last great thing to admire in this movie. Giovanni Lombardi Radice is Ricky is a close second, definitely, but Deodato made great use of his one night of location shooting. Anyway, back to this fucking movie.So they get to the party and when Lisa isn't leading Alex on (once the man gets naked, you'll have a hard time buying that any Annie Belle character would ever want to sleep with him - he's like 200 pounds of hairy, shameless ham) the rest of the guests take turns ridiculing Ricky and cheating him at cards. Alex gets fed up with their shit and decides he's going to just mess with everyone instead. This is where, I believe, the script was thrown out. Alex and Ricky find themselves in sexual situations with every girl present and at no point does any of it come off as motivated by the story. Alex rapes Lisa, but it's filmed like any soft core sex scene from the previous decade. Then Ricky is instructed to rape one of the other guests, but can't bring himself to do it. A little later she tries to escape and then they do have sex, though it's her idea...? Then a girl called Cindy shows up and Alex rapes and kills her in front of everyone else. And by this point he's humiliated everyone present, but of course our guests get the upper hand eventually and shoot Alex's dick off, but only after he's accidentally killed Ricky who was trying to get his friend to show some compassion. And then we find out what we should have guessed all along, that the girl from the beginning (remember her? You're not likely to if you're seeing the movie for the first time because Deodato does everything in his not inconsiderable power to make you forget you've seen anything other than whatever new horrible thing he's dreamt up) is actually Tom's sister.

Ruggero Deodato has what I call the Rob Zombie problem. He's a great filmmaker at his best, but he has never made a film I'd watch twice. His craft is wasted on some of the most vile pieces of trash that the Italian exploitation industry have to offer the movie-watching public. Starting with Jungle Holocaust, he embarked on a streak of movies that dare you not to flinch that only Franco Prosperi has rivaled, although seeing as how Deodato is personally responsible for every image he created, that stacks the deck in his favour as the better filmmaker. Prosperi went looking for horrifying imagery as often as he thought it up; Deodato was a man possessed by a singular vision when it came to messing you up good. Now this of course makes his movies ever more problematic. He was a better and smarter director than his contemporaries with more skill and care at his command which means he had a greater responsibility. With House On The Edge Of The Park he totally blew it. He took the premise, clearly intended as a Last House rip-off, and decided that rather than make an intelligent post-modern horror film he was going to focus on making single scenes make you queasy or turn you on, and didn't really care how it all fit together. Logistically speaking the big twist derails the whole plot. Why would Tom sit by and watch Alex rape his friends if he had a gun in the other room and was planning on using it the whole time? Why, if everyone was in on it, would they play along for so long even as they were humiliated, beaten and sexually assaulted? The simple answer is that Deodato didn't give a good goddamn about any of that. He was most interested in whatever was happening at that moment and if that didn't work for you, who the fuck cares? In his defense, was anyone going to House On The Edge Of The Park for the subtext? Well, me, but these days I rarely run into people like me who ask more of horror films.

Ruggero Deodato has what I call the Rob Zombie problem. He's a great filmmaker at his best, but he has never made a film I'd watch twice. His craft is wasted on some of the most vile pieces of trash that the Italian exploitation industry have to offer the movie-watching public. Starting with Jungle Holocaust, he embarked on a streak of movies that dare you not to flinch that only Franco Prosperi has rivaled, although seeing as how Deodato is personally responsible for every image he created, that stacks the deck in his favour as the better filmmaker. Prosperi went looking for horrifying imagery as often as he thought it up; Deodato was a man possessed by a singular vision when it came to messing you up good. Now this of course makes his movies ever more problematic. He was a better and smarter director than his contemporaries with more skill and care at his command which means he had a greater responsibility. With House On The Edge Of The Park he totally blew it. He took the premise, clearly intended as a Last House rip-off, and decided that rather than make an intelligent post-modern horror film he was going to focus on making single scenes make you queasy or turn you on, and didn't really care how it all fit together. Logistically speaking the big twist derails the whole plot. Why would Tom sit by and watch Alex rape his friends if he had a gun in the other room and was planning on using it the whole time? Why, if everyone was in on it, would they play along for so long even as they were humiliated, beaten and sexually assaulted? The simple answer is that Deodato didn't give a good goddamn about any of that. He was most interested in whatever was happening at that moment and if that didn't work for you, who the fuck cares? In his defense, was anyone going to House On The Edge Of The Park for the subtext? Well, me, but these days I rarely run into people like me who ask more of horror films. House On The Edge Of The Park is an unpleasant experience, but it's too dumb to be much harm. If you let it, it could probably get under your skin and watching my dad's reaction proves that, but these movies only have so much power and I do think that everyone has a point at which they can no longer be effected, your brain just doesn't allow you to get worked up anymore. It's seen enough! It stops seeing problems and just starts looking for things you like. And while I see that Deodato definitely has skill, I found nothing to like about House, which is a double-edged sword. After all, there are no comical fuck-ups, just upsetting ones that ruin the movie. When your brain looks for joy and finds none, it makes for a long hour and a half, but such is the tragedy of the completist. But, there is hope for us determined nutjobs. For instance, just as I was preparing to write this here confessional, I got word that there was one more Last House rip-off I hadn't seen. It was by Joe D'Amato, of all people, my personal favourite Italianate lunatic and when the summary on IMDB is misspelled, you know you're in for a rare treat. Suddenly the future seemed bright. Joe's take on the cannibal film is easily the most palatable of them all, so natch his Last House rip-off would surely make them all seem small by comparison. This film would restore all that was right and good in the world! It would reunite The Smiths! It would free Leonard Peltier from prison! It would make the Democratic Party stop behaving like such pussies and shove healthcare and equal rights bills up the GOP's ass and into the laps of the American public! And all this from a hardcore pornographic remake of a rip-off of a shitty Wes Craven film!

House On The Edge Of The Park is an unpleasant experience, but it's too dumb to be much harm. If you let it, it could probably get under your skin and watching my dad's reaction proves that, but these movies only have so much power and I do think that everyone has a point at which they can no longer be effected, your brain just doesn't allow you to get worked up anymore. It's seen enough! It stops seeing problems and just starts looking for things you like. And while I see that Deodato definitely has skill, I found nothing to like about House, which is a double-edged sword. After all, there are no comical fuck-ups, just upsetting ones that ruin the movie. When your brain looks for joy and finds none, it makes for a long hour and a half, but such is the tragedy of the completist. But, there is hope for us determined nutjobs. For instance, just as I was preparing to write this here confessional, I got word that there was one more Last House rip-off I hadn't seen. It was by Joe D'Amato, of all people, my personal favourite Italianate lunatic and when the summary on IMDB is misspelled, you know you're in for a rare treat. Suddenly the future seemed bright. Joe's take on the cannibal film is easily the most palatable of them all, so natch his Last House rip-off would surely make them all seem small by comparison. This film would restore all that was right and good in the world! It would reunite The Smiths! It would free Leonard Peltier from prison! It would make the Democratic Party stop behaving like such pussies and shove healthcare and equal rights bills up the GOP's ass and into the laps of the American public! And all this from a hardcore pornographic remake of a rip-off of a shitty Wes Craven film!Hard Sensations

by Joe D'Amato

After an unbearably long credits sequence we meet our heroes, three girls who are being chaperoned by their super hot professor Mrs. Perez to an island for two weeks of relaxation after exams. And seeing as how all the girls are rich, their fathers have arranged for the two burly guys who operate the boat to the island to stay and mind them. Well they could have used three for no sooner have the girls started swimming topless and having pillow fights then three criminals show up on their island having just broken out of the joint! They kill the guards and look like their poised to do more but Clyde, the most levelheaded of the bunch, reminds them that murder, prison break and the remainder of whatever sentences they skipped out on will be bad enough without rape factored in. This holds up for awhile but Bobo, the real asshole of the bunch, can't chill his libido for another second longer and when he decides to shake things up, Mrs. Perez takes the bullet and sleeps with him hoping upon hope that it will keep him from attacking the girls. But soon not even Clyde's handwringing can curb Bobo's various lusts and he and their third companion tie Clyde to a tree and Bobo has his pick of the women. But of course, they've already started planning their escape.

After an unbearably long credits sequence we meet our heroes, three girls who are being chaperoned by their super hot professor Mrs. Perez to an island for two weeks of relaxation after exams. And seeing as how all the girls are rich, their fathers have arranged for the two burly guys who operate the boat to the island to stay and mind them. Well they could have used three for no sooner have the girls started swimming topless and having pillow fights then three criminals show up on their island having just broken out of the joint! They kill the guards and look like their poised to do more but Clyde, the most levelheaded of the bunch, reminds them that murder, prison break and the remainder of whatever sentences they skipped out on will be bad enough without rape factored in. This holds up for awhile but Bobo, the real asshole of the bunch, can't chill his libido for another second longer and when he decides to shake things up, Mrs. Perez takes the bullet and sleeps with him hoping upon hope that it will keep him from attacking the girls. But soon not even Clyde's handwringing can curb Bobo's various lusts and he and their third companion tie Clyde to a tree and Bobo has his pick of the women. But of course, they've already started planning their escape.Thank christ and all his angels for Joe D'Amato. The man does smut right! And best of all even the things that go wrong (surprisingly few, actually) they don't particularly matter because this is a filthy goddamned porn film! But, as I don't watch porn for the same reason most of the rest of the world watches porn, I can enjoy its latent qualities! The dubbing in Joe's films is always pretty good and even though people talk in platitudes, they sound less forced and awkward then they would in a Jesus Franco film, at least. And there's even convincing overlap rather than the standard gigantic pauses between any two lines; it almost sounds like real conversation. The script makes sense: Clyde is legitimately smart about their situation and Bobo is as deranged as any of the protagonist of any of the last five films we've discussed. And here's a semi-interesting diversion: one of the escapees is gay. And because Bobo the rapist is the one who's seen as irredeemable, Joe gets in one for acceptance by giving him all the epithets. Bobo only ever refers to his second accomplice as "the faggot" and for once homosexuality isn't a source of derisive laughter, it's just something that separates a rapist from a criminal. Taken together that's almost progressive as these things get, especially because Hard Sensation plays almost like a corrective to The Last House on the Beach.

With Hard Sensation Joe was faced with a dilemma: sex film vs. rape revenge film. The script was a retread of Beach and so calls for a certain level of violence but Joe was a zany humanist first, a lover of onscreen violence second. Frankly I'd love to know what the assignment was because violence definitely didn't win out. In fact if you take out the snapping and threats that start all but one of them and the rape in this film is about the gentlest example of rape you'll find in any movie. Joe didn't quite have the heart to follow through on the violence part of the sexual violence equation, so each rape turns into a straight-up sex scene, not because Joe viewed rape as something you could rebound from or enjoy, but because all he was interested in was filming sex scenes just as Ruggero Deodato was only interested in violence, his commitment didn't extend beyond keeping the plot alive when the clothes came off. The sex scenes are all of the consenting variety, even if afterwards everyone acts like something much worse happened. Joe's attitude toward sex might be called classical; the plot is window dressing and he's not going to let it get in the way of sex scenes his audience could rely on. The raincoat crowd was going to leave happy this time and the horror fans would have to wait for Anthropophagous, but bless him for spinning the most believable of all the Italian Last House clones when he wasn't filming sex scenes! Forgive me for sweeping the issue of rape under the carpet here, but considering that every one of the above films (Dead End Street excluded) treats rape pornographically on a thematic if not physical and very real level, Hard Sensations is almost refreshing. Not just because Joe doesn't make the audience suffer for his art, but because he was the only one of these guys to actually follow through and show sex as it is, rather than lie and use rape as only a justification for the lamest revenge scenes of any film.

With Hard Sensation Joe was faced with a dilemma: sex film vs. rape revenge film. The script was a retread of Beach and so calls for a certain level of violence but Joe was a zany humanist first, a lover of onscreen violence second. Frankly I'd love to know what the assignment was because violence definitely didn't win out. In fact if you take out the snapping and threats that start all but one of them and the rape in this film is about the gentlest example of rape you'll find in any movie. Joe didn't quite have the heart to follow through on the violence part of the sexual violence equation, so each rape turns into a straight-up sex scene, not because Joe viewed rape as something you could rebound from or enjoy, but because all he was interested in was filming sex scenes just as Ruggero Deodato was only interested in violence, his commitment didn't extend beyond keeping the plot alive when the clothes came off. The sex scenes are all of the consenting variety, even if afterwards everyone acts like something much worse happened. Joe's attitude toward sex might be called classical; the plot is window dressing and he's not going to let it get in the way of sex scenes his audience could rely on. The raincoat crowd was going to leave happy this time and the horror fans would have to wait for Anthropophagous, but bless him for spinning the most believable of all the Italian Last House clones when he wasn't filming sex scenes! Forgive me for sweeping the issue of rape under the carpet here, but considering that every one of the above films (Dead End Street excluded) treats rape pornographically on a thematic if not physical and very real level, Hard Sensations is almost refreshing. Not just because Joe doesn't make the audience suffer for his art, but because he was the only one of these guys to actually follow through and show sex as it is, rather than lie and use rape as only a justification for the lamest revenge scenes of any film. And bless him for all the little Joe D'Amato touches that litter Hard Sensation. First of all the sex scenes all take place on the same island as Erotic Nights of the Living Dead and Porno Holocaust. At the start one of the girls reads Playgirl magazine - a first for Italian smut as far as I can tell. The masturbation that follows borrow liberally from the Jesus Franco school of zooming in and out like a goddamned pervy lunatic. And who but Joe could have dreamt up shooting the final rape scene from behind Bobo's thigh? There is just more imagination on display here than in movies with ten times the budget and pretension. If you take all the unbearable self-important bullshit that props up every film in the wake of Last House on the Left, including Last House itself, you have enough talk to prop up a piece of paper. Which is to say, your ideas are fucking nothing if you don't have the intelligence to make anything of them. The reason Joe D'Amato of all people makes these "serious artists" and their serious minded films seem like the tall-talking jagweeds they truly are is that he never once made a bigger deal of his movies than he knew they could support. If you don't understand your subject matter, how could you rise above it long enough to gain any kind of perspective? Joe had no pretensions and so he entertains because it's what he was born to do. He knew there was no point in getting haughty about porn and in the process of churning out a truly staggering body of work bared his soul completely inadvertently. How could you not? It's moments like this that I live for. I know what you're thinking: What the fuck kind of maniac goes this crazy for a goddamned Joe D'Amato porn film? Well, readers, I've seen too many assholes retroactively try and turn their shit grindhouse movies into one of the great masterpieces of the twentieth century, so for once I'm sticking up for the factory filmmaker, the littlest little guy who never claimed to be anything other than the little guy, if he ever took the time to reflect on his career at all. Christ knows he didn't reflect on the films after he was done shooting once a few things were securely in place. And yet, Hard Sensation is hands down the best Last House rip-off ever made. Go figure. And weirder still I haven't committed to seeing everything he's ever done. Maybe I'm cured...

And bless him for all the little Joe D'Amato touches that litter Hard Sensation. First of all the sex scenes all take place on the same island as Erotic Nights of the Living Dead and Porno Holocaust. At the start one of the girls reads Playgirl magazine - a first for Italian smut as far as I can tell. The masturbation that follows borrow liberally from the Jesus Franco school of zooming in and out like a goddamned pervy lunatic. And who but Joe could have dreamt up shooting the final rape scene from behind Bobo's thigh? There is just more imagination on display here than in movies with ten times the budget and pretension. If you take all the unbearable self-important bullshit that props up every film in the wake of Last House on the Left, including Last House itself, you have enough talk to prop up a piece of paper. Which is to say, your ideas are fucking nothing if you don't have the intelligence to make anything of them. The reason Joe D'Amato of all people makes these "serious artists" and their serious minded films seem like the tall-talking jagweeds they truly are is that he never once made a bigger deal of his movies than he knew they could support. If you don't understand your subject matter, how could you rise above it long enough to gain any kind of perspective? Joe had no pretensions and so he entertains because it's what he was born to do. He knew there was no point in getting haughty about porn and in the process of churning out a truly staggering body of work bared his soul completely inadvertently. How could you not? It's moments like this that I live for. I know what you're thinking: What the fuck kind of maniac goes this crazy for a goddamned Joe D'Amato porn film? Well, readers, I've seen too many assholes retroactively try and turn their shit grindhouse movies into one of the great masterpieces of the twentieth century, so for once I'm sticking up for the factory filmmaker, the littlest little guy who never claimed to be anything other than the little guy, if he ever took the time to reflect on his career at all. Christ knows he didn't reflect on the films after he was done shooting once a few things were securely in place. And yet, Hard Sensation is hands down the best Last House rip-off ever made. Go figure. And weirder still I haven't committed to seeing everything he's ever done. Maybe I'm cured...