Kwaidan

by Masaki Kobayashi

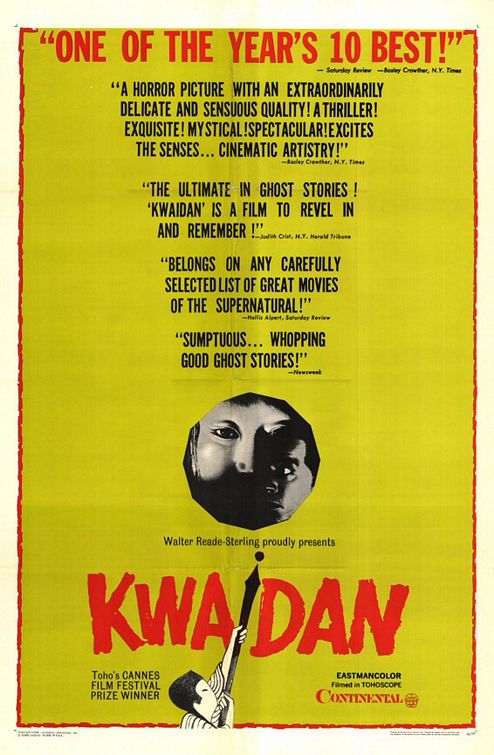

Masaki Kobayashi knew hardship more than most; though he despised violence, he was sent to the frontlines of World War II and refused promotion because he didn’t want to compromise his beliefs and for his troubles he was taken prisoner (something he supposed to kill himself before he allowed to happen, but if he wasn’t going to take a promotion you can bet he wasn’t taken a sword to the gut either). When he returned he became a film director; a hired gun making pretty dull sounding dramatic pieces. It wasn’t until the late 50s that he made the film he wanted to make, a three piece, nine-hour plus epic called The Human Condition, a dramatization of his experiences in the war. It was lofty, to be sure, but what it proved to everyone was how exquisite a storyteller Kobayashi really was. After making the universally revered Harakiri or Seppuku with his Human Condition leading man Tatsuya Nadakai, he and his team made their first color film, one of the most spectacular, haunting films ever made. I’ve seen more horror films than I know how to sort through, and Kwaidan (which means ghost story) is without competition. Based on stories by Lacfadio Hearn, globetrotting collector of folk tales, Kwaidan is a rarity in Japan’s cinematic legacy: a three hour horror anthology with little to no dialogue, shot in feverish color, where the existence of ghosts is an unspoken truth and in which each story has an identical story arc. Before I being I’d like to say that every visual and sound in this film is perfect. Every last one.

Masaki Kobayashi knew hardship more than most; though he despised violence, he was sent to the frontlines of World War II and refused promotion because he didn’t want to compromise his beliefs and for his troubles he was taken prisoner (something he supposed to kill himself before he allowed to happen, but if he wasn’t going to take a promotion you can bet he wasn’t taken a sword to the gut either). When he returned he became a film director; a hired gun making pretty dull sounding dramatic pieces. It wasn’t until the late 50s that he made the film he wanted to make, a three piece, nine-hour plus epic called The Human Condition, a dramatization of his experiences in the war. It was lofty, to be sure, but what it proved to everyone was how exquisite a storyteller Kobayashi really was. After making the universally revered Harakiri or Seppuku with his Human Condition leading man Tatsuya Nadakai, he and his team made their first color film, one of the most spectacular, haunting films ever made. I’ve seen more horror films than I know how to sort through, and Kwaidan (which means ghost story) is without competition. Based on stories by Lacfadio Hearn, globetrotting collector of folk tales, Kwaidan is a rarity in Japan’s cinematic legacy: a three hour horror anthology with little to no dialogue, shot in feverish color, where the existence of ghosts is an unspoken truth and in which each story has an identical story arc. Before I being I’d like to say that every visual and sound in this film is perfect. Every last one.Now, don’t take any of those qualities to mean this is anything short of stunning. The first story The Black Hair shows a samurai who leaves his wife to find fortune, only to realize that he was happier as a married pauper than he is dealing with the squabbles of the rich. He returns several years later and finds his wife right where he left her, exactly the same, except for one small detail. The second story The Snow Woman features Kobayashi’s frequent lead Tatsuya Nadakai as Minokichi an 18-year-old pilgrim (just three years after he played a sexagenarian in Harakiri) and his master who are caught in a blizzard. They seek refuge from the snow in a hut by a river, but the small building doesn’t do much to keep the cold out, or a tall ghastly woman who breathes on the old man, killing him instantly. The woman makes to do the same to Minokichi, but stops, inspecting his youthful countenance and liking what she sees. She tells him that she will let him live as long as he never tells anyone about the events of that evening. Understandably he agrees and it seems Minokichi’s luck has turned around; he meets a beautiful girl who bears him three children and the two of them lead a prosperous life. One night, the light hits his bride’s face just right and it reminds him of something he never told anyone…

The third story Hoichi The Earless has an image I have never seen bested anywhere. The story unfolds after a battle at sea between the Heike and Genji clans ends with in the death of all involved (the battle scene is unbelievable). Because the site of the battle is supposed to be haunted, a Buddhist temple was built near the site of both the battle and the cemetery where the collected bodies were buried. Hoichi, a blind attendant at the temple is left by himself one night and uses the time to play his biwa, a four-stringed instrument, and sing about the epic battle his bosses were placed to pray over. Well, before too long Hoichi gains an audience of one, after a giant armored man appears from the mist and request Hoichi play for his master, a man of real prestige. Not wanting to offend this powerful man, Hoichi obliges again and again, each time becoming weaker and weaker. Well, before long the head priest (Takashi Shimura, who was in just about every Kurosawa film ever made) is alerted to the ritual, he and his partner can think of only one solution (those of you who’ve seen this picture know what I’m talking about). They paint him from head to toe in a scripture designed to make him invisible to evil spirits, but because nothing horrific has happened yet, we know some grave misfortune is about to befall poor Hoichi; ghosts don’t take no for an answer. The fourth and final story In A Cup Of Tea is both a ghost story and a comment about Japanese literature. An author is cataloging old folk tales (not unlike the ones we’re being told) and stumbles upon one that is only half finished. It concerns a samurai who while on duty makes to drink a cup of tea, but, much to his displeasure, he sees a pale, maniacally smiling face in the reflection of the beverage. Try as this man does, he can’t get rid of the face. Not knowing what else to do, the samurai drinks the tea and the face inside it. That night while on guard duty someone pays him a return visit, and he’s not alone. Before the story closes, we are brought back to the author telling this story, who has a guest of his own. When his landlady can’t find him, she just about has a heart attack when she looks in the old man’s teapot.

Kwaidan, an extension of the prose with which Kobayashi presented the inner conflicts of man and his struggle with societal pressure, is different from any other project he would ever involve himself with. The only horror film he ever attempted, Kwaidan (pronounced Kai-dan) is like a filmic version of one of the songs Hoichi plays on his biwa. Indescribably terrible things happen but their beauty (at least, to a lot of dead Japanese sailors) prevents us from diverting our attention for even a minute. The score here (all nerve-wracking percussion, from the clanking during the Black Hair to the aforementioned Biwa) deserves an oscar for it’s ability to instill fear independent of the images (one of many this film earned but never saw). Interestingly (to me, anyway) the stories Kobayashi chose to film weren’t meant strictly to scare. Two of the tales taken from Hearn’s many volumes on Japanese lore, the Snow Woman and The Black Hair are almost identical to two stories used as fuel for another Japanese filmic masterpiece, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu. Mizoguchi took two parables from Japanese history (as well as one French short story) and tweaked them to craft a broader narrative, which became Ugetsu. The first, The House In The Thicket by Akinari Ueda is about a young man who leaves his wife behind, believing her to have died when samurai besieged their town. When he returns many years later, she is there, just as he left her, but by morning is gone again. Now, granted Kobayashi’s version doesn’t end with an elegy trading between the husband and a neighborhood monk, but the stories are basically the same. The other, A Serpent’s Lust has much in common with the Snow Woman. Japanese films have a history of reinterpretation almost as notorious as American films (Kihachi Okamoto’s Kill! Is a retelling of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, itself a filmic version of Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest; the 47 Ronin have had as many films made about them, etc.), and so it’s interesting to see that the same stories can give birth to retellings and inspired tales so wildly different in Japan that it puts the best American remakes to shame.

Kwaidan, an extension of the prose with which Kobayashi presented the inner conflicts of man and his struggle with societal pressure, is different from any other project he would ever involve himself with. The only horror film he ever attempted, Kwaidan (pronounced Kai-dan) is like a filmic version of one of the songs Hoichi plays on his biwa. Indescribably terrible things happen but their beauty (at least, to a lot of dead Japanese sailors) prevents us from diverting our attention for even a minute. The score here (all nerve-wracking percussion, from the clanking during the Black Hair to the aforementioned Biwa) deserves an oscar for it’s ability to instill fear independent of the images (one of many this film earned but never saw). Interestingly (to me, anyway) the stories Kobayashi chose to film weren’t meant strictly to scare. Two of the tales taken from Hearn’s many volumes on Japanese lore, the Snow Woman and The Black Hair are almost identical to two stories used as fuel for another Japanese filmic masterpiece, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu. Mizoguchi took two parables from Japanese history (as well as one French short story) and tweaked them to craft a broader narrative, which became Ugetsu. The first, The House In The Thicket by Akinari Ueda is about a young man who leaves his wife behind, believing her to have died when samurai besieged their town. When he returns many years later, she is there, just as he left her, but by morning is gone again. Now, granted Kobayashi’s version doesn’t end with an elegy trading between the husband and a neighborhood monk, but the stories are basically the same. The other, A Serpent’s Lust has much in common with the Snow Woman. Japanese films have a history of reinterpretation almost as notorious as American films (Kihachi Okamoto’s Kill! Is a retelling of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, itself a filmic version of Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest; the 47 Ronin have had as many films made about them, etc.), and so it’s interesting to see that the same stories can give birth to retellings and inspired tales so wildly different in Japan that it puts the best American remakes to shame.

Kwaidan, an extension of the prose with which Kobayashi presented the inner conflicts of man and his struggle with societal pressure, is different from any other project he would ever involve himself with. The only horror film he ever attempted, Kwaidan (pronounced Kai-dan) is like a filmic version of one of the songs Hoichi plays on his biwa. Indescribably terrible things happen but their beauty (at least, to a lot of dead Japanese sailors) prevents us from diverting our attention for even a minute. The score here (all nerve-wracking percussion, from the clanking during the Black Hair to the aforementioned Biwa) deserves an oscar for it’s ability to instill fear independent of the images (one of many this film earned but never saw). Interestingly (to me, anyway) the stories Kobayashi chose to film weren’t meant strictly to scare. Two of the tales taken from Hearn’s many volumes on Japanese lore, the Snow Woman and The Black Hair are almost identical to two stories used as fuel for another Japanese filmic masterpiece, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu. Mizoguchi took two parables from Japanese history (as well as one French short story) and tweaked them to craft a broader narrative, which became Ugetsu. The first, The House In The Thicket by Akinari Ueda is about a young man who leaves his wife behind, believing her to have died when samurai besieged their town. When he returns many years later, she is there, just as he left her, but by morning is gone again. Now, granted Kobayashi’s version doesn’t end with an elegy trading between the husband and a neighborhood monk, but the stories are basically the same. The other, A Serpent’s Lust has much in common with the Snow Woman. Japanese films have a history of reinterpretation almost as notorious as American films (Kihachi Okamoto’s Kill! Is a retelling of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, itself a filmic version of Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest; the 47 Ronin have had as many films made about them, etc.), and so it’s interesting to see that the same stories can give birth to retellings and inspired tales so wildly different in Japan that it puts the best American remakes to shame.

Kwaidan, an extension of the prose with which Kobayashi presented the inner conflicts of man and his struggle with societal pressure, is different from any other project he would ever involve himself with. The only horror film he ever attempted, Kwaidan (pronounced Kai-dan) is like a filmic version of one of the songs Hoichi plays on his biwa. Indescribably terrible things happen but their beauty (at least, to a lot of dead Japanese sailors) prevents us from diverting our attention for even a minute. The score here (all nerve-wracking percussion, from the clanking during the Black Hair to the aforementioned Biwa) deserves an oscar for it’s ability to instill fear independent of the images (one of many this film earned but never saw). Interestingly (to me, anyway) the stories Kobayashi chose to film weren’t meant strictly to scare. Two of the tales taken from Hearn’s many volumes on Japanese lore, the Snow Woman and The Black Hair are almost identical to two stories used as fuel for another Japanese filmic masterpiece, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu. Mizoguchi took two parables from Japanese history (as well as one French short story) and tweaked them to craft a broader narrative, which became Ugetsu. The first, The House In The Thicket by Akinari Ueda is about a young man who leaves his wife behind, believing her to have died when samurai besieged their town. When he returns many years later, she is there, just as he left her, but by morning is gone again. Now, granted Kobayashi’s version doesn’t end with an elegy trading between the husband and a neighborhood monk, but the stories are basically the same. The other, A Serpent’s Lust has much in common with the Snow Woman. Japanese films have a history of reinterpretation almost as notorious as American films (Kihachi Okamoto’s Kill! Is a retelling of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, itself a filmic version of Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest; the 47 Ronin have had as many films made about them, etc.), and so it’s interesting to see that the same stories can give birth to retellings and inspired tales so wildly different in Japan that it puts the best American remakes to shame. Before I go I have to speak about the best image this movie has to offer; that of Hoichi covered in the Japanese characters. It is arrestingly beautiful and terrifying in its own right. This image would be haunting in any movie but with the wonderful scene composition Kobayashi provides – the impending horror, the scary music – the image is made thousands of times more urgent. And when Hoichi is called to move about when he is jostled around by the warrior’s ghost, he looks unreal, like a computer generated image, making the scene even more dreamlike and stunning. And no, you don’t get a picture from me, go find the movie and see it for yourself, to see it before hand is to do cheat.

Before I go I have to speak about the best image this movie has to offer; that of Hoichi covered in the Japanese characters. It is arrestingly beautiful and terrifying in its own right. This image would be haunting in any movie but with the wonderful scene composition Kobayashi provides – the impending horror, the scary music – the image is made thousands of times more urgent. And when Hoichi is called to move about when he is jostled around by the warrior’s ghost, he looks unreal, like a computer generated image, making the scene even more dreamlike and stunning. And no, you don’t get a picture from me, go find the movie and see it for yourself, to see it before hand is to do cheat.

No comments:

Post a Comment