The Face Of Another

by Hiroshi Teshigahara

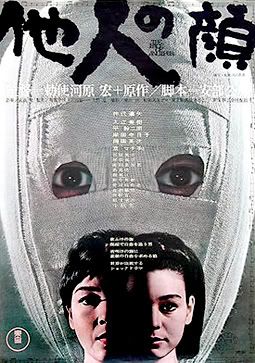

This film owes a significant debt to another black-and-white psychological horror film; Georges Franju’s The Face Of Another. Those of you who’ve seen it should know then the subject matter dealt with in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s artistic tale of loss and alienation causing the mind to turn stale is not exactly groundbreaking, but it was still effective, especially in the context of post-war Japan. The story, based on a novel by Kobo Abe, someone director Teshigahara had an informal partnership with for the first ten years of his career, follows two people affected by cosmetic disorder. The first, a man called Okuyama (a particularly crazy Tatsuya Nakadai) has been disfigured by an industrial accident and now has a bandage covering his entire face (the implication seems to be that it is permanent). The second, far less developed story follows a woman with a radiation burn on one half of her otherwise beautiful face. These stories, in case you couldn’t tell, are really about Hiroshima and the loss of identity that followed. Okuyama, who we will primarily concern ourselves with is one sick dude. He purposely bugs his wife because he knows that he repulses her and makes a point of unnerving everyone he comes in contact with (talk about self-pity). The answer to his problems (or the beginning, depending on how you look at it) comes when he meets a nameless psychologist who moonlights as a plastic surgeon. Together they come up with a plan – mold a mask for Okuyama out of someone else’s likeness and give the scarred man a new face. Now the psychiatrist, understands just how dangerous such a procedure is (“it’s like a drug that turns you invisible”) and knows Okuyama is probably going to do some truly ghastly things with his new face, but he’s too tittilated by the prospect of studying him to say no. So, against his and his nurse/mistress’ better judgment, they craft a face for Okuyama, and unsurprisingly Okuyama becomes unrecognizable, physically and mentally, to everyone with two exceptions: the mentally handicapped daughter of a hotel manager and someone I won’t mention, as it would ruin the film for you. I will say this, both act as Okuyama’s undoing as the real reason he decided to adopt the new visage was to try and seduce his wife to teach her a lesson, but that doesn’t exactly pan out. The second story, of the girl with the hideous burn on her face could be in any Italian modernist film of the 1960s in its minimalist intensity. She moves from location to location, experience-varying degrees of mistreatment, deciding ultimately that she was not meant for the world – such a world where a war could start at any moment. It isn’t exactly linear logic, but it uses pretty effective imagery.

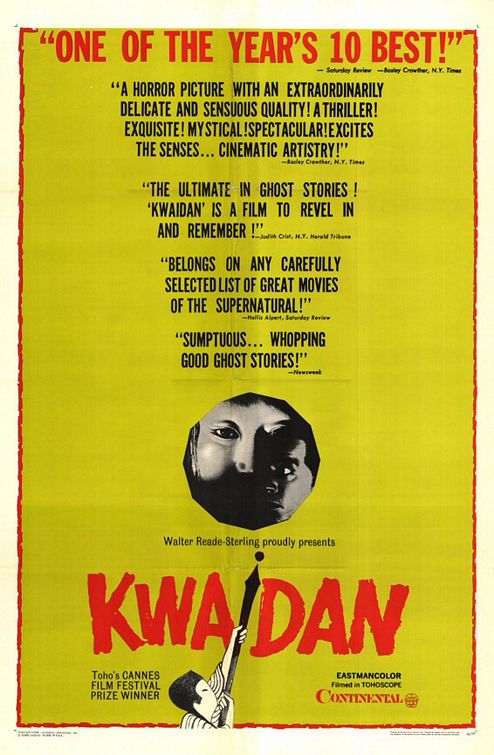

This film owes a significant debt to another black-and-white psychological horror film; Georges Franju’s The Face Of Another. Those of you who’ve seen it should know then the subject matter dealt with in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s artistic tale of loss and alienation causing the mind to turn stale is not exactly groundbreaking, but it was still effective, especially in the context of post-war Japan. The story, based on a novel by Kobo Abe, someone director Teshigahara had an informal partnership with for the first ten years of his career, follows two people affected by cosmetic disorder. The first, a man called Okuyama (a particularly crazy Tatsuya Nakadai) has been disfigured by an industrial accident and now has a bandage covering his entire face (the implication seems to be that it is permanent). The second, far less developed story follows a woman with a radiation burn on one half of her otherwise beautiful face. These stories, in case you couldn’t tell, are really about Hiroshima and the loss of identity that followed. Okuyama, who we will primarily concern ourselves with is one sick dude. He purposely bugs his wife because he knows that he repulses her and makes a point of unnerving everyone he comes in contact with (talk about self-pity). The answer to his problems (or the beginning, depending on how you look at it) comes when he meets a nameless psychologist who moonlights as a plastic surgeon. Together they come up with a plan – mold a mask for Okuyama out of someone else’s likeness and give the scarred man a new face. Now the psychiatrist, understands just how dangerous such a procedure is (“it’s like a drug that turns you invisible”) and knows Okuyama is probably going to do some truly ghastly things with his new face, but he’s too tittilated by the prospect of studying him to say no. So, against his and his nurse/mistress’ better judgment, they craft a face for Okuyama, and unsurprisingly Okuyama becomes unrecognizable, physically and mentally, to everyone with two exceptions: the mentally handicapped daughter of a hotel manager and someone I won’t mention, as it would ruin the film for you. I will say this, both act as Okuyama’s undoing as the real reason he decided to adopt the new visage was to try and seduce his wife to teach her a lesson, but that doesn’t exactly pan out. The second story, of the girl with the hideous burn on her face could be in any Italian modernist film of the 1960s in its minimalist intensity. She moves from location to location, experience-varying degrees of mistreatment, deciding ultimately that she was not meant for the world – such a world where a war could start at any moment. It isn’t exactly linear logic, but it uses pretty effective imagery. This is the least scary and most meditative of all the films reviewed here (and Kwaidan is pretty meditative), but that’s because it was the only one made by a card carrying new waver. Hiroshi Teshigahara made precious few films in his lifetime, but those that he did were designed to burn bridges and break hearts. The Face of Another or Tanin No Gao has very few scares in it – and the ones in there mostly derive from just how upsetting it is to see Okuyama probing the depths of personal space. The strange shape of his bandaged head makes every movement a nerve wracking one. This film is incredibly interesting because of the bizarre mixture of elements and influences – The similarities between Okuyama’s appearance and that of The Invisible Man, The bizarre design of the plastic surgeon’s office (which really has to be seen, it’s amazing), the appearance of projected images on doors and windows, the nod to Chris Marker’s La Jetee at the end of the girl’s story, the symmetry that exists between Okuyama’s life and that of his new face, the very perplexing issues brought up by the surgeon as he watches someone with no redeeming qualities live with no boundaries and the extent to which he is willing to help in order to live vicariously through Okuyama – it really is a provocative film. The design and cinematography and execution are pure 60s art house, but the subject matter and imagery are of another school altogether, one I’m not sure I can place. The film’s main purpose is to show just dark it gets inside the soul when the thing that everyone sees, the face, is purposely ignored. Take that humanity!

I’d like to take a moment to discuss Tatsuya Nakadai, the star of half of the above entries. As this movie has an operation that significantly changes the psyche of its main character, discussion of a mad scientist is inevitable. The surgeon in this movie however is not him. No, the mad scientist behavior belongs to Okuyama, who only lacks any real scientific knowledge. His mannerisms, inflection, behavior and logic all seem to belong to Dr. Frankenstein or Pretorius or some such mad genius. Nakadai was about as versatile an actor as you could find in the 60s and doesn’t get nearly the credit he deserves (not that a mention on a blog concerned with Zombie movies is going to give it to him). It’s because Nakadai was such a strong actor that his character far outweighs everyone around him and even though he is an unsympathetic bastard, you can’t help but wish him to succeed. Nadakai’s first real acting job came in Kobayashi’s aforementioned Human Condition trilogy, extraordinary films that don’t feel their length. Many have heralded them as the best films ever made and they certainly deserve all the praise they receive (any film with pacing decent enough to make 9 hours seem justifiable deserves all the acclaim it can get). There are two exceptional things about these movies. The first is that they are not, like Musashi Miyamoto or most other Japanese epics, based on a sprawling prose-filled novel, they’re based (loosely) on Kobayashi’s life. Second is that he is such an eloquent and skilled storyteller. The second goes a long way toward explaining the absolutely gorgeous Kwaidan. The other thing that makes these films remarkable is that they are carried by Tatsuya Nakadai, who not four years ago had been an extra in Seven Samurai. It takes real talent to move up that quickly in the film world, and Nakadai could have built a house with his. Watch him in his two early Okamoto films the Sword Of Doom and Kill! He goes from being the very definition of evil to perfectly deadpanning his funniest role in a satire of the samurai films that have made him a star.

I’d like to take a moment to discuss Tatsuya Nakadai, the star of half of the above entries. As this movie has an operation that significantly changes the psyche of its main character, discussion of a mad scientist is inevitable. The surgeon in this movie however is not him. No, the mad scientist behavior belongs to Okuyama, who only lacks any real scientific knowledge. His mannerisms, inflection, behavior and logic all seem to belong to Dr. Frankenstein or Pretorius or some such mad genius. Nakadai was about as versatile an actor as you could find in the 60s and doesn’t get nearly the credit he deserves (not that a mention on a blog concerned with Zombie movies is going to give it to him). It’s because Nakadai was such a strong actor that his character far outweighs everyone around him and even though he is an unsympathetic bastard, you can’t help but wish him to succeed. Nadakai’s first real acting job came in Kobayashi’s aforementioned Human Condition trilogy, extraordinary films that don’t feel their length. Many have heralded them as the best films ever made and they certainly deserve all the praise they receive (any film with pacing decent enough to make 9 hours seem justifiable deserves all the acclaim it can get). There are two exceptional things about these movies. The first is that they are not, like Musashi Miyamoto or most other Japanese epics, based on a sprawling prose-filled novel, they’re based (loosely) on Kobayashi’s life. Second is that he is such an eloquent and skilled storyteller. The second goes a long way toward explaining the absolutely gorgeous Kwaidan. The other thing that makes these films remarkable is that they are carried by Tatsuya Nakadai, who not four years ago had been an extra in Seven Samurai. It takes real talent to move up that quickly in the film world, and Nakadai could have built a house with his. Watch him in his two early Okamoto films the Sword Of Doom and Kill! He goes from being the very definition of evil to perfectly deadpanning his funniest role in a satire of the samurai films that have made him a star.

He did everything – comedy, drama, horror, sword play – nothing was too much for Nakadai, and beneath those hollow eyes was someone who could make you believe he was suffering for all of humanity or chillingly making all of humanity suffer. Though Toshiro Mifune gets most of the credit (though I surmise this has more to do with him being older and getting an early start with Rashamon and Seven Samurai. Not that he isn’t terrific…) as Japan’s leading man, I’d almost always prefer Nakadai, who with ten times the subtlety of his grumbling peer gave just as splendid a performance.