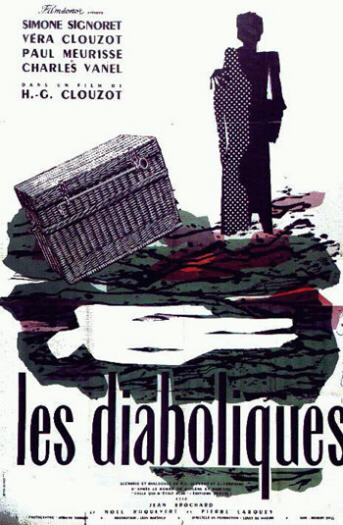

Diabolique

by Henri-Georges Clouzot

Christine and Nicole are two very tired looking teachers at a boarding school in a small French village. The reason for their drawn appearances is that they’re both locked in what appear to be very tumultuous relationships with the same man, Christine’s husband Michel, the principle of the school. Christine has been aware of Nicole’s affair with her husband for some time, to the point that she’s started offering her tips to deal with her husband’s ill temper and foul mannerisms. He’s clearly made both of their lives miserable, as exemplified by a pretty disgusting display at dinner with their colleagues (not to mention all their students) present. Just when you begin to think that maybe these two ought to do something, they do. In fact they’ve been planning to kill Michel for some time. The plan goes something like this: they drive out to an apartment that the two women have rented as both their alibi and as an out of the way place to do the deed in relative secrecy. Christine will call Michel and threaten to divorce him; not wanting to invite that kind of embarrassment, he’ll come out to reason with his long-suffering wife. Once he arrives they drug him, drown him in the bath, put him in an old wicker trunk, put his body in the school swimming pool and wait for him to surface, their hands apparently blood-free. It sounds like the perfect plan, but this wouldn’t exactly be a fright film if it were.

Christine has a number of doubts, many brought on by her heart condition. She’s worried that the stress of the operation might just cause her poor ticker to give out and it nearly does from the look on her face as she gives her husband wine that Nicole poisoned earlier that day. There are a couple of near-misses involved in bringing the corpse from their room to the pool and once Michel’s body is at the bottom the pool becomes a fixation for Christine; she can’t stop obsessing over it, staring at it during class and experiencing palpitations whenever anyone goes near it. Finally she and Nicole are granted an excuse to uncover the last phase of their plan when something falls into the pool and one of the boys who swims after it comes up with the principle’s cigarette lighter. Imagine both womens’ shock when the pool is emptied and the man they left there is absent. Though I guess it makes a certain kind of sense; after all, only someone with an intimate knowledge of the crime could begin leaving hints that Michel is still alive for Christine and Nicole to find, like when the suit they drowned him shows up pressed and cleaned at the school. Christine and Nicole do some investigating and very quickly they determine that either someone found the body and moved it or something went wrong with their plan. The third option, that Michel has come back from the grave to haunt them, seems just as ridiculous to them as it probably does to you, but when even the students begin seeing him around the school reason and logic are no longer the comfort they once were.

Christine has a number of doubts, many brought on by her heart condition. She’s worried that the stress of the operation might just cause her poor ticker to give out and it nearly does from the look on her face as she gives her husband wine that Nicole poisoned earlier that day. There are a couple of near-misses involved in bringing the corpse from their room to the pool and once Michel’s body is at the bottom the pool becomes a fixation for Christine; she can’t stop obsessing over it, staring at it during class and experiencing palpitations whenever anyone goes near it. Finally she and Nicole are granted an excuse to uncover the last phase of their plan when something falls into the pool and one of the boys who swims after it comes up with the principle’s cigarette lighter. Imagine both womens’ shock when the pool is emptied and the man they left there is absent. Though I guess it makes a certain kind of sense; after all, only someone with an intimate knowledge of the crime could begin leaving hints that Michel is still alive for Christine and Nicole to find, like when the suit they drowned him shows up pressed and cleaned at the school. Christine and Nicole do some investigating and very quickly they determine that either someone found the body and moved it or something went wrong with their plan. The third option, that Michel has come back from the grave to haunt them, seems just as ridiculous to them as it probably does to you, but when even the students begin seeing him around the school reason and logic are no longer the comfort they once were.

The greatest strength that the film has is that you the viewer are presented with the same set of facts as our heroes. We experience the ups and downs of the plan right along with the girls because we know what a cad Michel is and we want poor, pretty Véra Clouzot (the director’s wife and favorite leading lady until her death of a heart attack in 1960, poor thing) and sassy Simone Signoret to come out on top. When we start receiving the clues left by whomever is out to get Christine and Nicole, they are just as shocking to us as they are to them. Granted, I’m speaking in something like generalities; I had the misfortune to have the ending ruined for me before I ever got a chance to see the movie, for which I blame Showtime’s 100 Greatest Horror Movies and John Motherfucking Landis. Anyway, the first time I saw one of the final menacing clues (it involves a school picture) I couldn’t help feeling like the bottom had dropped out of my stomach, even though I knew where the film was going. I can only imagine how much more effective it would have been if I’d actually been in the dark because as it is it's extremely effective. The picture and of course the conclusion are pitch-perfect. Unlike American or British films of the same vintage, the film is played entirely straight. Christine and Nicole and everyone else for that matter are all firmly grounded in reality; even at the end when it seems like something truly sinister can only account for the mischief we’ve seen, Christine refuses to believe in anything but what she can see (her background as a nun helps drive home her reluctance to believe in anything, especially as I strongly suspect Michel was directly responsible for her fall from grace). No one ever jumps to conclusions, in fact no one but Christine, Nicole and the detective they hire called Fichet ever knows anything’s at all wrong. Christine has to put up a front of innocence while everything she takes for granted slips away. In essence, it’s the first film I can think of where massive fits of hysteria and superstition don’t immediately plague our heroes. Even when the supernatural seems to be the only possible answer, Christine doesn’t want to believe it.

All this is just a round about way of saying that this film, its director Henri-Georges Clouzot and its intended audience were all smart. Clouzot plays up the evils of humanity, even in the children who attend the boarding school, so that when he pulls the rug out from under you at the end you’ll be shocked but prepared. His script is amazing; every line of dialogue, no matter how trivial, every single tangent serves the plot and his investigation of the crime is just as clever as the crime itself. And to keep everyone grounded in reality while things spiral out of control, his direction is very straight forward (if nicely composed). The performances are uniformly great down to the bit players and the film is, with the exception of one shot of Christine running down the school hallways at night during the film’s conclusion, completely free of artifice or anything to suggest that what we’re seeing isn’t really happening. Yet even lacking stylish editing or expressionistic shadowplay the film manages to be just as creepy and effective as anything produced in Germany at the height of the 20s. Clouzot knew that what is most frightening is what’s around us and what people are capable of and even with an incredibly frightening conclusion, what we’re supposed to take away from all this is that people are the most frightening thing in the world. So while the film straddles the line between mystery and horror (yet still maintaining a masterful feeling of suspense) it can’t really be called either without selling its finest aspects short. Clouzot was a tremendous filmmaker who refused to just make a genre film, whose ideas went beyond what we typically associate with ordinary stories and made some of the most riveting films in history that despite being mostly a half century old haven’t aged a day. If you haven’t seen the film, run, don’t walk, but don’t let the world ruin its ending for you because there is nothing quite so satisfying as letting something so wonderful and spellbinding frighten the hell out of you the one time that it can. Diabolique gets to the core of why fright films are so tremendous, the magic, if you will that comes from a good scare. Sometimes, when a plot is lovingly crafted and the scares are so carefully planned, it just feels great to turn the lights out and let a master auteur do what he does best.

So while the film straddles the line between mystery and horror (yet still maintaining a masterful feeling of suspense) it can’t really be called either without selling its finest aspects short. Clouzot was a tremendous filmmaker who refused to just make a genre film, whose ideas went beyond what we typically associate with ordinary stories and made some of the most riveting films in history that despite being mostly a half century old haven’t aged a day. If you haven’t seen the film, run, don’t walk, but don’t let the world ruin its ending for you because there is nothing quite so satisfying as letting something so wonderful and spellbinding frighten the hell out of you the one time that it can. Diabolique gets to the core of why fright films are so tremendous, the magic, if you will that comes from a good scare. Sometimes, when a plot is lovingly crafted and the scares are so carefully planned, it just feels great to turn the lights out and let a master auteur do what he does best.

All this is just a round about way of saying that this film, its director Henri-Georges Clouzot and its intended audience were all smart. Clouzot plays up the evils of humanity, even in the children who attend the boarding school, so that when he pulls the rug out from under you at the end you’ll be shocked but prepared. His script is amazing; every line of dialogue, no matter how trivial, every single tangent serves the plot and his investigation of the crime is just as clever as the crime itself. And to keep everyone grounded in reality while things spiral out of control, his direction is very straight forward (if nicely composed). The performances are uniformly great down to the bit players and the film is, with the exception of one shot of Christine running down the school hallways at night during the film’s conclusion, completely free of artifice or anything to suggest that what we’re seeing isn’t really happening. Yet even lacking stylish editing or expressionistic shadowplay the film manages to be just as creepy and effective as anything produced in Germany at the height of the 20s. Clouzot knew that what is most frightening is what’s around us and what people are capable of and even with an incredibly frightening conclusion, what we’re supposed to take away from all this is that people are the most frightening thing in the world.

So while the film straddles the line between mystery and horror (yet still maintaining a masterful feeling of suspense) it can’t really be called either without selling its finest aspects short. Clouzot was a tremendous filmmaker who refused to just make a genre film, whose ideas went beyond what we typically associate with ordinary stories and made some of the most riveting films in history that despite being mostly a half century old haven’t aged a day. If you haven’t seen the film, run, don’t walk, but don’t let the world ruin its ending for you because there is nothing quite so satisfying as letting something so wonderful and spellbinding frighten the hell out of you the one time that it can. Diabolique gets to the core of why fright films are so tremendous, the magic, if you will that comes from a good scare. Sometimes, when a plot is lovingly crafted and the scares are so carefully planned, it just feels great to turn the lights out and let a master auteur do what he does best.

So while the film straddles the line between mystery and horror (yet still maintaining a masterful feeling of suspense) it can’t really be called either without selling its finest aspects short. Clouzot was a tremendous filmmaker who refused to just make a genre film, whose ideas went beyond what we typically associate with ordinary stories and made some of the most riveting films in history that despite being mostly a half century old haven’t aged a day. If you haven’t seen the film, run, don’t walk, but don’t let the world ruin its ending for you because there is nothing quite so satisfying as letting something so wonderful and spellbinding frighten the hell out of you the one time that it can. Diabolique gets to the core of why fright films are so tremendous, the magic, if you will that comes from a good scare. Sometimes, when a plot is lovingly crafted and the scares are so carefully planned, it just feels great to turn the lights out and let a master auteur do what he does best.

1 comment:

Well thank you terribly, old man. I'll keep writing if you keep reading, eh?

Post a Comment