Time of the Wolf

by Michael Haneke

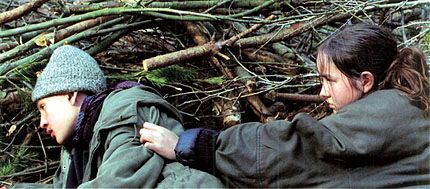

Anne and Georges Laurent are headed to their secluded cabin with their children Ben and Eva to wait out the crisis that's taken hold of Paris (and presumably, though it's never stated, the rest of the world). They've apparently fled just in time and too late for once they get to the cabin they find a family already living there. When Georges tries reasoning with them, the head of the squatter family shoots him dead in front of Anne and the children. Anne, Ben and Eva leave with only a bicycle to store their food and belongings (including Ben's parakeet) on. They get to the nearest village and ask some former friends and neighbors for help but as supplies are low and have no hope of replenishing their generosity toward the newly widowed Anne isn't exactly boundless. The Laurents take shelter in a wooden shack in the middle of a field until the night Ben goes missing. They build a fire to try and draw him back but predictably it burns out of control while Anne goes out into the darkness to look for her son and when she returns there isn't much of the shack left. The next morning he does come back, but he's not alone; a homeless boy about Eva's age shows up with a knife at Ben's throat and tries to trade him for supplies. Anne is too good a mother to let the boy leave on his own so once she gets her son back she offers to let the other boy stay with them as they try to find help. The boy reluctantly agrees and says he knows of a place where trains carrying supplies are supposed to go so they set off for the station that day.

Anne and Georges Laurent are headed to their secluded cabin with their children Ben and Eva to wait out the crisis that's taken hold of Paris (and presumably, though it's never stated, the rest of the world). They've apparently fled just in time and too late for once they get to the cabin they find a family already living there. When Georges tries reasoning with them, the head of the squatter family shoots him dead in front of Anne and the children. Anne, Ben and Eva leave with only a bicycle to store their food and belongings (including Ben's parakeet) on. They get to the nearest village and ask some former friends and neighbors for help but as supplies are low and have no hope of replenishing their generosity toward the newly widowed Anne isn't exactly boundless. The Laurents take shelter in a wooden shack in the middle of a field until the night Ben goes missing. They build a fire to try and draw him back but predictably it burns out of control while Anne goes out into the darkness to look for her son and when she returns there isn't much of the shack left. The next morning he does come back, but he's not alone; a homeless boy about Eva's age shows up with a knife at Ben's throat and tries to trade him for supplies. Anne is too good a mother to let the boy leave on his own so once she gets her son back she offers to let the other boy stay with them as they try to find help. The boy reluctantly agrees and says he knows of a place where trains carrying supplies are supposed to go so they set off for the station that day.The train very quickly proves to be less than the saving grace the young scavenger believes it to be. It passes them on their way and not only does it not stop, there doesn't seem to be anyone on board. They reach the station not long after and find a group of survivors led by a monsieur Koslowski who looks like Jean Renoir and because for whatever reason he's in charge he abuses what little power that entitles him to. His interactions with the Brandts, a married couple, pretty much show you what people think of him. Lise (played by Trouble Every Day and À l'intérieur's Béatrice Dalle) hates him and constantly belittles him; Thomas, thinking his wife's insolence is going to get them kicked out of their shelter, makes a big show of berating her in front of everyone. The young scavenger doesn't particularly like taking orders so instead he lives in the woods nearby; Eva visits him every now and again to make sure he doesn't go hungry while they wait for another train to pass through the station. Before anything can really come to a head, an enormous group of people shows up with horses, goats and guns.

Koslowski kisses his power goodbye and what little space the survivors enjoyed is now encroached upon by about a dozen families, all of them waiting for the same train that may never get there. Despite the large group's proficiency for order two conflicts arrise soon after they settle in, the first when the young boy steals one of the goats they had been using for milk. The next when Eva recognizes one of the newcomers as the man who shot her dad. Anne and Eva want justice but have no proof beyond their word that the man and by extension his whole family is guilty of murder. This absense of justice (and the many others floating around) has led many of the survivors to find comfort in wild mystical theories about 'chosen' people. Ben listens as some of the older travelers spin wild tales about these people who survive walking through fire and persecution so they can bring hope to those who need it most. Wanting dearly to do so, Ben gets it in his head that he too must walk through fire. And who's to say he's wrong with so much death, lawlessness and hopelessness everywhere? His act of bravery and selflessness could be what people need while waiting for a train that promises salvation but may never come.

There are a lot of movies I'd like to make people like Michael Bay, Akiva Goldsman and Paul W.S. Anderson sit down and watch and Time of the Wolf is at the top of that list. Once again I'll come clean and say that this post-apocalyptic fable isn't exactly a horror or sci-fi film. It's a revisionist dystopian movie set in an endless grayish-green landscape featuring excellently understated and realistic performances and whose villain is simply the evils of of human nature. In other words it is approximately my favorite kind of film. Haneke understands that you don't need a billion dollars or CG vampires to make a good post-apocalyptic film. Time looks like it was made for nothing and achieves its barren atmosphere not in what it shows you but what it doesn't show you. Haneke had proven how strongly he disapproved of movie violence and spectacle in Funny Games so relies only on people and their inability to act humane as the focal point of what could be called the fright.

There are a lot of movies I'd like to make people like Michael Bay, Akiva Goldsman and Paul W.S. Anderson sit down and watch and Time of the Wolf is at the top of that list. Once again I'll come clean and say that this post-apocalyptic fable isn't exactly a horror or sci-fi film. It's a revisionist dystopian movie set in an endless grayish-green landscape featuring excellently understated and realistic performances and whose villain is simply the evils of of human nature. In other words it is approximately my favorite kind of film. Haneke understands that you don't need a billion dollars or CG vampires to make a good post-apocalyptic film. Time looks like it was made for nothing and achieves its barren atmosphere not in what it shows you but what it doesn't show you. Haneke had proven how strongly he disapproved of movie violence and spectacle in Funny Games so relies only on people and their inability to act humane as the focal point of what could be called the fright.Haneke returns to this theme quite a bit, as in Caché and The White Ribbon, and drives home the point as often as he can, that the only thing we need to fear are people who see others as means to an end. There's an apparent nod to Andrei Tarkovski's Andrei Rublev that spells this out; the newcomers are low on food so they shoot the horses just as unceremoniously as Georges Laurent is killed at the start of the film. The man who shot Georges is dangerous because his view of human life is just as unfeeling as the others' view of the horses. Eva and Anne watch the slaughter of the horses with just as much unease as if they were watching Georges die again and again. Though they seek justice for their loss I feel what they and Haneke both want is for people to treat each other as equals. Koslowski's petty abuse of power has the same despicable character as he simply wields something he found first like a weapon. He seems content to treat other people like shit so long as they respect him, which is why the arrival of the newcomers is more than a small victory because he's impotent without property to lord over his tenants (marxist justice if ever there was any). The newcomers make everyone equal again, but they can't make everyone care about human life, which is why the young scavenger still steals the goat from them. You cannot make people care; you can simply care for them and hope that they will come around to your way of thinking (a Randian shrew trying to prove he knows how to survive best of anybody, because he seems to enjoy stealing and surviving without anyone's help). Hence why Eva never stops trying to help the boy; her father died trying to protect both her and her borther so they seem forever destined to try and protect other people. Their simple and often stilted acts of altruism are much more poignant and interesting than ten thousand gunfights or battles with special effects. Haneke's film, though simple and inexpensive, is years ahead of other modern tales about the end of life because it's just about people; that's all he cares about which makes his movies both incredibly dark and optimistic all at once. That's not to say some spectacle is out of the question (Children of Men proves that beyond a shadow of a doubt) but really there must be a human story at the heart of all of it. The power to do good, to solve the greatest of crises is inside every person, they just have to embrace it. That is what Haneke seems to have broadcasted since his first film and conversely, what happens when you reject it.

Of course the only problem I find with movies so deeply routed in the everyday lives and of people is that the action can become a little monotonous. I could have done with a touch more from the characters in the second and third acts. Once they arrive at the station Ben is almost abandoned by the story until the final scene and the young scavenger is not shown doing enough to make me believe he survives the whole time. And though I get it's an age-old tradition to kill horses for films and it drives his thesis home, I feel Haneke could have not actually killed those horses and still made a beautiful film. Other than that....that's it, really, I love this movie. Not a lot happens but it's gorgeous and poetic and realistic and really excellent. Isabelle Huppert is great as usual but the heart of the film is Anaïs Demoustier as Eva. She's sneering and angry for a good part of her screentime but when she loses that exterior like when she writes a letter to her dead father or cries in front of the scavenger, she's brilliant. Haneke's ability to get naturalistic and believable performances from actors is amazing and the crisis of faith he examines throughout the course of the film is visible on Demoustier's face. His examination of our need for belief in the afterlife wouldn't work with a more pious set of characters but it works with the very ordinary Laurent family.

The last thing that Haneke does that really puts him above his peers is his take on religion. The stories that influence Ben about the chosen, the arrival of the train and Eva's letter to her dad are all ways to hypothesize about the after life without guessing about its existence or trying to tell you what to think. Contrast this with I Am Legend's sent-by-god speech and it’s like there’s a clear line between good filmmaking and bad right there in their respective tacks. He doesn't drive anything home, he merely shows the merit of differing belief systems and then rather than saying that we must think this or it's better to think that, he shows that the only thing that's truly important is being brave enough to help those you care about. Ben's final act is thus the leap of faith that proves that he believes in people and a belief in god or a higher calling is irrelevant. He acts out of love and hope. The final shots can be seen as transcendence of the plain of misery the characters are trapped in because Ben has shown himself worthy of being saved and we're treated to the only sunny day of the film and the beauty of such a simple thing is greater than anyone's vision of paradise; the train means hope for people and what else could you ask for?

The last thing that Haneke does that really puts him above his peers is his take on religion. The stories that influence Ben about the chosen, the arrival of the train and Eva's letter to her dad are all ways to hypothesize about the after life without guessing about its existence or trying to tell you what to think. Contrast this with I Am Legend's sent-by-god speech and it’s like there’s a clear line between good filmmaking and bad right there in their respective tacks. He doesn't drive anything home, he merely shows the merit of differing belief systems and then rather than saying that we must think this or it's better to think that, he shows that the only thing that's truly important is being brave enough to help those you care about. Ben's final act is thus the leap of faith that proves that he believes in people and a belief in god or a higher calling is irrelevant. He acts out of love and hope. The final shots can be seen as transcendence of the plain of misery the characters are trapped in because Ben has shown himself worthy of being saved and we're treated to the only sunny day of the film and the beauty of such a simple thing is greater than anyone's vision of paradise; the train means hope for people and what else could you ask for?

No comments:

Post a Comment