Irréversible

by Gaspar Noé

The events of the film are, for some reason, shown backwards. I'm going to guess that its because Gaspar Noé wants us to examine how the night went and that the simplest of things led to its outcome. So, here's how we see it. First two men, one thin the other fat and in his underwear (the ubiquitous Phillippe Nahon, who like star Vincent Cassel, was in Mathieu Kassovitz' excellent La Haine). They talk about how time ruins everything, cause that's the moral. Then we see a guy called Marcus (Cassel) get wheeled out of a gay bar called Rectum on a gurney. A man called Pierre is put in handcuffs while the police shout homophobic things at the two of them. We then go backwards in time about fifteen minutes; first we get a whiplash inducing tour of Rectum, where we see the sex acts of the men while a drone-like soundtrack plays and the lowlight gives way to bursts of nightmarish red where we glimpse the occasional hint of something illicit. Then Marcus shows up with a nervous Pierre in tow looking for a guy with the nickname The Tapeworm, so you can guess how seriously everyone takes him. He finds someone who may or may not be the guy and picks a fight with him, which Marcus loses in about fifteen seconds. The guy who might be the tapeworm starts to try to rape Marcus, but Pierre beats the man with a fire extinguisher until his face is not really a face at all (it's pretty unendurable to watch). Then we go back and see Pierre and Marcus looking for the club in a taxi that they steal.

The events of the film are, for some reason, shown backwards. I'm going to guess that its because Gaspar Noé wants us to examine how the night went and that the simplest of things led to its outcome. So, here's how we see it. First two men, one thin the other fat and in his underwear (the ubiquitous Phillippe Nahon, who like star Vincent Cassel, was in Mathieu Kassovitz' excellent La Haine). They talk about how time ruins everything, cause that's the moral. Then we see a guy called Marcus (Cassel) get wheeled out of a gay bar called Rectum on a gurney. A man called Pierre is put in handcuffs while the police shout homophobic things at the two of them. We then go backwards in time about fifteen minutes; first we get a whiplash inducing tour of Rectum, where we see the sex acts of the men while a drone-like soundtrack plays and the lowlight gives way to bursts of nightmarish red where we glimpse the occasional hint of something illicit. Then Marcus shows up with a nervous Pierre in tow looking for a guy with the nickname The Tapeworm, so you can guess how seriously everyone takes him. He finds someone who may or may not be the guy and picks a fight with him, which Marcus loses in about fifteen seconds. The guy who might be the tapeworm starts to try to rape Marcus, but Pierre beats the man with a fire extinguisher until his face is not really a face at all (it's pretty unendurable to watch). Then we go back and see Pierre and Marcus looking for the club in a taxi that they steal.We then see that the reason the two men are after someone called the tapeworm is because two imposing guys take Marcus and Pierre on a tour of a street filled with prostitutes. They find a hermaphrodite called Guillermo who, at knife point, tells them she saw a guy called the Tapeworm do 'it'. We learn what 'it' is when we go back a few minutes more and see a woman being wheeled into an ambulance. Marcus loses it because the woman is his wife, Alex (Monica Bellucci, whose beauty is almost implausible, to the point that she looks like a special effect); they tell him that she was raped and is now in a coma. Then the two imposing guys find him and say they found a purse near the scene of the crime with Guillermo's ID in it. Then we see Alex get attacked in a tunnel just trying to cross the street. Some guy sees that Guillermo is not strictly a woman and flips out and grabs Alex instead and rapes her at knife point and then beats her nearly to death. We see all of this in one nine minute tracking shot. I don't often look away from movie screens, but I did and I'm not in the least ashamed to admit it. We then see her leaving a party because Marcus's behavior embarrasses her. Then we see Marcus, Pierre and Alex on the subway headed for the party. Then we see Marcus and Alex relaxing at home. Then we see Alex by herself in a park where children play. Then the words "Time Ruins Everything" display after an obnoxious strobe light takes over the screen. This happens because we saw a 2001: A Space Odyssey poster on Alex's wall and because apparently Gaspar Noé thinks he's Stanley Kubrick. He's not...at best he's Jeunet by way of some reverse-Kenneth Anger, with a 99th of the creativity and none of his love for people.

That is the whole film and the moral is simple: see that every little action we perform has major consequences, or maybe everything's random. Noé also seems to say that something nice in the morning will suck at night. I think that that's kinda childish, but then, maybe he just means to say that all good things have to end. But really my question is what moral could possibly be worth nine fucking minutes of watching a woman get raped at knife-point? None, that's what. I don't give a good goddamn if you've discovered the meaning of life, I'll pass if it means watching a woman get raped in real time. I know it's a film, I know it's not real, and I also know that this happens every day but that doesn't mean I want to see that or any approximation of it on screen because though I do come to arthouse cinema (especially a film like this which screams "Look how fucking meaningful I am!", which is pretty bold considering the notion that rape really sucks has been in films since 1929 when Alfred Hitchcock made Blackmail! about precisely that, which is why this movie makes me extra furious. This film is shot entirely from the pornographic male gaze and yet thinks it's message can weather its misogyny; to contrast one vision of a naked heroine with another as high and low points of existence isn't what I'd call progressive, even if it makes artistic sense. Just what did Noé think he was accomplishing?) expecting to be taught a lesson in humanity or at the very least filmmaking, I do not think that just because you can does not mean you should. And I don't think that his using the sexual habits of gay men as a point of vulgarity quite in this way is really acceptable either. It gets treated with the same, if not more, otherness and contempt than the rape and homosexuals are treated like deviants. And maybe Noé is just commenting on how we perceive sexuality. If so, maybe he should given some indication he doesn't identify with is presentation of homosexuals because I have no reason not to think he believes everything he put on the screen.

The best I can say for this film is that it's well directed. Not as well directed as 2001: A Space Odyssey (which I didn't even really like) or Delicatessen or most art films, but Noé does some interesting things with the camera and though the decision to go backwards was kind of interesting, it was not unique nor totally necessary. The pre-rape afterglow between Bellucci and Cassel is gorgeously shot and feels real and acts as a foil to the harsher subject matter. But you know what...he could have said all this and more without being a repugnant prat. So any compliment I could pay his direction is moot because I disagree with his ideas 100%. It's possible to comment on something without sinking as low as you're subject matter but in this game of Name That Taboo....Now Break It that french directors started playing, it's really hard to want to go looking for the meaning in something so grotesque, especially if it involves rape at knife point, or as in the next film, toothpoint.

The best I can say for this film is that it's well directed. Not as well directed as 2001: A Space Odyssey (which I didn't even really like) or Delicatessen or most art films, but Noé does some interesting things with the camera and though the decision to go backwards was kind of interesting, it was not unique nor totally necessary. The pre-rape afterglow between Bellucci and Cassel is gorgeously shot and feels real and acts as a foil to the harsher subject matter. But you know what...he could have said all this and more without being a repugnant prat. So any compliment I could pay his direction is moot because I disagree with his ideas 100%. It's possible to comment on something without sinking as low as you're subject matter but in this game of Name That Taboo....Now Break It that french directors started playing, it's really hard to want to go looking for the meaning in something so grotesque, especially if it involves rape at knife point, or as in the next film, toothpoint. Trouble Every Day

by Claire Denis

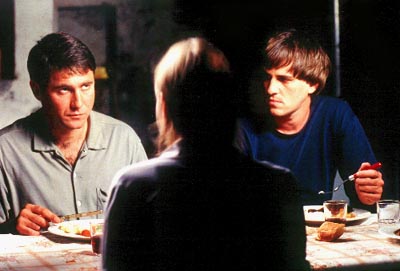

The story of Trouble Every Day is told in fragmented interactions and incidents so if you're not vigilant you'll probably fall behind. The oddly captivating Coré (Béatrice Dalle, who've seen previously in À l'intérieur, and who we'll see again in Time of the Wolf) flags down a truck driver with her eyes. A little later, Dr. Léo Semeneau (Alex Descas, a favorite of Jim Jarmusch, look for him in Coffee & Cigarettes and The Limits of Control), a man we'll later learn is her husband, shows up and finds the man dead and Coré covered in his blood. He doesn't seem horrified as you or might if we happened upon the same thing. His resigned reaction to it signifies to me that he's used to this sort of thing. The next morning before heading off to work he hands her pills, which she throws away the second his back is turned. When he leaves for work, she pulls a jigsaw from under the bed and cuts her way out of her locked bedroom. Elsewhere American newlyweds Shane and June Brown arrive in Paris for their honeymoon, or so it seems. Shane keeps having flashes of poor June making eyes at him while covered in blood. When he admits to her later that he has to meet with some clinicians, one gets the sense that perhaps Paris was not chosen as the location of their honeymoon simply for the beautiful architecture and romantic dining options.

The story of Trouble Every Day is told in fragmented interactions and incidents so if you're not vigilant you'll probably fall behind. The oddly captivating Coré (Béatrice Dalle, who've seen previously in À l'intérieur, and who we'll see again in Time of the Wolf) flags down a truck driver with her eyes. A little later, Dr. Léo Semeneau (Alex Descas, a favorite of Jim Jarmusch, look for him in Coffee & Cigarettes and The Limits of Control), a man we'll later learn is her husband, shows up and finds the man dead and Coré covered in his blood. He doesn't seem horrified as you or might if we happened upon the same thing. His resigned reaction to it signifies to me that he's used to this sort of thing. The next morning before heading off to work he hands her pills, which she throws away the second his back is turned. When he leaves for work, she pulls a jigsaw from under the bed and cuts her way out of her locked bedroom. Elsewhere American newlyweds Shane and June Brown arrive in Paris for their honeymoon, or so it seems. Shane keeps having flashes of poor June making eyes at him while covered in blood. When he admits to her later that he has to meet with some clinicians, one gets the sense that perhaps Paris was not chosen as the location of their honeymoon simply for the beautiful architecture and romantic dining options.Across town Coré is at it again; Léo, after discovering a house full of sawdust, a missing car and a missing wife, goes looking for her in the usual spot and has to bury another guy. Meanwhile Shane goes looking for Léo in his old place of work but is met with a bunch of vague bullshit from his old colleagues who seem to know that the American can only be up to no good. He gets an address from a lab tech who meets him in private and heads for Léo's house. We're told in flashback that he and Coré once had an affair while Léo was conducting some research involving plants and people. That's where they met and while it seems reasonable that Shane just wants to see Coré again, I sense something more sinister is afoot. I should also mention that Shane isn't the only one interested in getting into Léo's house. Two kids have been casing the place, convinced that all the chemistry in the basement is about making meth, not a cure for his wife's insanity. One of them finds Coré and tears off the boards her husband nailed up to keep her indoors and the two begin making love, at which point everything becomes clear. Coré can't just have sex with someone, you see. Somethings gone wrong in her head and now she cannot be satisfied unless she eats some of her bedmate. What do you think the odds are that Shane may be also have this same malady and that in order to make love to his wife, he has to cure it? What do you think's going to happen when the former lovers reunite?

I feel kind of embarrassed for both me and Claire Denis that the first thing that came to mind while watching this was "This is kinda like Cannibal Apocalypse..." And while I love a good John Saxon movie and I appreciate a movie that can pay tribute in a quiet, scientific way (I'm looking at you Quentin Tarentino), I don't think this was the effect Denis was going for. Trouble Every Day is slow and told in broken pieces, the effect is that if you weren't an ace at mad science in movies, you'll probably have some questions by the time the word "Fin" rolls around. I rather like the plot (and unlike the Antonio Margheriti film it most resembles, it's satisfying rather than a mishmash of a bunch of prior cannibal film elements) and the sort of sleepwalking pace (though as a friend pointed out, the music, by melodramatic lounge act Tindersticks, is just awful. It plays like film noir, which would be fine if the action were fast-paced but its not, so this achingly slow music just calls attention to how slow everything else is) but I part company with Denis on a few issues. First is the extent to which we see the combination of cannibalism and intercourse; actually make that everything. I don't need to see Vincent Gallo biting that poor woman's urethra and I don't need to see him masturbate (you don't quite the eyeful that you do in Gallo's film The Brown Bunny, but you do get a pretty good view of his fake semen. What's with this guy and his penis?). Also, how do we go from one guy dead in Coré's bed to a wall coated in viscera? Not that it isn't a cool image and all...And my biggest complaint is that there's no conclusion. I want to see how Shane and his wife live now that Shane's embraced his wild side. I want to know what Léo does with all this attention brought on by Shane and his wife. I want to know how June copes with Shane's disease. I want to know the things that Denis is less interested in. This being a film of extremes, she was more interested in hinting at plot points and showing us blood and semen, which is interesting coming from a female perspective. It's all interesting, but I have questions that a mosaic of AB negative can't answer.

Other than getting by mostly on implication, the film suffers from unattractive cinematography and a plot a little more conventional than it seems at first. Denis plays a game of reveals, seeing how little she can give away while the imagery becomes more immediate and violent. The film is not (with the exception of that music) self-important or laden with messages, it simply asks how far some of us will go to feel pleasure. It's not love, as the silly slogan implies, it's just about pleasure. Shane and his wife could and have theoretically gotten on fine without sex (in fact, that begs the question: had they had sex at all before getting married?) but Shane is after flesh, in both senses of the word. In fact that he knowingly married someone he liked makes him a pretty big asshole because he knows he has a tremendous mental issue to work out and she's going to necessarily get caught in the middle of it. In that regard, the disease can be likened to AIDS or any other degenerative STD, in that to sleep with the carrier means death. Of course, that sort of both oversimplifies and gives more credit to a cannibal film than perhaps it deserves. It's a strange film and it's combination of hazy detachment from the story and very uncomfortable, violent sexuality makes for an unconventional take on age-old subject matter. Not the best thing I've ever seen, but it's interest to me as a film goes a long way toward making up for its more repulsive scenes.

Other than getting by mostly on implication, the film suffers from unattractive cinematography and a plot a little more conventional than it seems at first. Denis plays a game of reveals, seeing how little she can give away while the imagery becomes more immediate and violent. The film is not (with the exception of that music) self-important or laden with messages, it simply asks how far some of us will go to feel pleasure. It's not love, as the silly slogan implies, it's just about pleasure. Shane and his wife could and have theoretically gotten on fine without sex (in fact, that begs the question: had they had sex at all before getting married?) but Shane is after flesh, in both senses of the word. In fact that he knowingly married someone he liked makes him a pretty big asshole because he knows he has a tremendous mental issue to work out and she's going to necessarily get caught in the middle of it. In that regard, the disease can be likened to AIDS or any other degenerative STD, in that to sleep with the carrier means death. Of course, that sort of both oversimplifies and gives more credit to a cannibal film than perhaps it deserves. It's a strange film and it's combination of hazy detachment from the story and very uncomfortable, violent sexuality makes for an unconventional take on age-old subject matter. Not the best thing I've ever seen, but it's interest to me as a film goes a long way toward making up for its more repulsive scenes.

You can make a point with extremes, it just becomes harder to take it seriously and so critics are far less willing to go looking for meaning....perhaps that's why the film recieved such poor treatment on DVD. Regardless, I use this as a counterpoint to Irréversible because though I had a hard time getting through both films without letting my eyes wander off the screen, Trouble Every Day manages to maintain its credibility by approaching sexuality and violence from a fantastic point-of-view. Cannibalism is not quite the horrendous crime that rape is (especially when it's fictitious), which means I can distance myself from the things on the screen a little better, which is important for me. I can't support a film like Irréversible and don't encourage anyone else to on moral grounds. I don't go to films because I need a reminder how dangerous it is for women to walk the streets and neither does anyone else. Women get lessons in subjugation from films like Transformers 2, I don't think art films need to take such an aggressive tack. I understand the need to challenge an audience but why should it have to be dangerous to walk into the cinema?