They Live

by John Carpenter

A nameless drifter rolls into Los Angeles looking for work; this man never gets a name so seeing as how he’s played by former wrestler Roddy Piper, we’ll just call him Roddy. After some wasted time at the unemployment office Roddy finds a job at a construction site. When his foreman yells at him about not sleeping on the job, Frank, one of his co-workers tells him about a shelter nearby where there’s hot food and showers. That night he notices a few odd goings on. First a phantom broadcast keeps interrupting the cable TV. A bearded man keeps ranting about ‘them’ and that they’ve been keeping us asleep and uninformed. Second is that men keep coming and going from the church across the street. He gets the run around from one of the men he asks and when he investigates he finds what seems unquestionably like something illegal. Amidst chemistry sets, piles of knock off Ray-Bans and stacks of cardboard boxes are men talking about moving products over the sound of a pre-recorded church choir. On the wall is a bit of graffiti, which in my opinion is the best thing about this movie “They Live We Sleep”. Roddy finally pisses off when a blind priest feels his face and tells him he wants to show him something – I guess I would, too. Later that night the police show up, raid the church, and then break up the hobo camp with their batons.

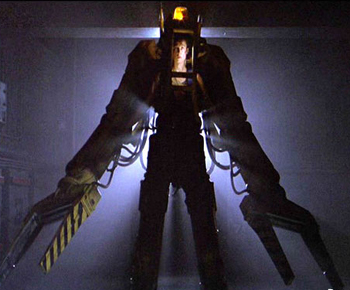

When Roddy goes back to the church he finds one box left. He seems a little disappointed when he finds out it’s just full of those same sunglasses. When he puts them on that disappointment turns to fascination and horror. First of all, everything’s in black and white. Second on the list of new sensations is that every thing that carries a slogan of any kind simply says “Buy”, “Obey” and “Submit” on it where there should be cheerful business talk. That means we’re treated to a view of every hippy’s perception of America, a street coated in big black and white billboards with big ominous words on them. Third and last, every third or fourth person he sees doesn’t look human at all. I’m not sure what Carpenter was going for with these guys but they look like the Mutant from This Island Earth via Jan Svankmajer. When Roddy starts calling it like he sees it (it starts with him making a scene in a supermarket, and then ends with him shooting up a bank), he discovers a few things. The bug men die when you shoot them, they all communicate through their wristwatches and can disappear whenever they please.

Roddy lets two people on this new phenomenon. The first is a woman named Holly Thompson who works for the cable TV station that the underground sunglass manufacturers were corrupting. He hops in her car and bums a ride at gunpoint. When they get back to her house, she brains him with a bottle of champaign and sends him flying out her second story window leaving the sunglasses and his crazy ass story behind. When he staggers back to town the next day he tells Frank about what he’s seen. Frank, a family man on the straight and narrow, wants nothing to do with a multiple murderer. The two men come to blows over whether Frank will where the sunglasses for what feels like an eternity and in the end Frank sees the light too. Terrified, the two men go looking for the resistance and then for the signal keeping everyone blind.

I’d like to say that They Live is a cult film, but I have no proof. It just seems like one from start to end. Larry Franco’s screenplay, which probably seemed really cool when he wrote it, doesn’t hold up, least of all with Carpenter’s weirdly static direction and Roddy Piper and Meg Foster’s ‘acting’. I feel like there ought to be an honorary cult status placed on this movie just through it’s mixture of badly functioning elements – isn’t that what cult films are all about? The makeup alone places this on Ed Wood’s plane. Franco’s screenplay calls for a lot of one-liners to be delivered with much manliness and a lot of Springsteen-esque anti-Reagan poverty talk to be delivered with much manly resolve. There aren’t characters so much as there are types – Roddy Piper is a working class Rambo type, Keith David who plays Frank is a family man with responsibility. Neither has much depth and both become one-note action heroes when the film hits the halfway mark. This is everyone’s fault, really. Keith David was better in The Thing and Roddy Piper isn’t actually an actor, so when depth is called for, he falls pretty short of the mark. Meg Foster who plays Holly is both disconcertingly weird looking and wooden. If Franco cared half as much about believable protagonists as it did for throwaway “Here I Am, Kill Me!” henchmen, this might have been a worthy successor to…well anything other than Big Trouble in Little China, but even there it falls short.

Carpenter is such an interesting director; like Wes Craven he loves youth culture and being politically active and his message is always topical it’s just that his execution always falls so short of relevance. Look at Escape From New York. Carpenter’s assertion that New York belonged to freaks that civilization wanted nothing to do with was a reality that kids were living with, his film just comes nowhere near the sort of lifestyle they were living. Carpenter makes films that typically place a lot of importance on the actions of a small group of people. They Live, The Thing, In The Mouth of Madness, Prince of Darkness, and Vampires all share this common thread, but They Live is the one that doesn’t have the gravity to back its apocalyptic nature. I guess because They Live is also sort of a satire, it spends less time being serious, but it’s still violent and weird and not nearly as funny as it thinks it is. They Live is a strange hybrid of all the styles of filmmaking he had ever dabbled in and is easily the least exciting of all the films he’s made. It’s still fun to watch, but a scene, let alone a movie, should never hinge on Roddy Piper’s facial expressions. Carpenter always picks very odd things to carry his films. For awhile this next movie was just ‘the pirate ghost’ movie to me. Now there’s a strange thing to base your film around.

The Fog

by John Carpenter

Before we start the review proper, I just want to point out how big into self-referencing Carpenter is. Horror directors are, the best known of them I should say, people who like working with the same crew over and over again. Starting in the 1980s, directors and writers sometimes got into the habit of naming their characters after genre people they idolized (hence why every character in Night of the Creeps shares a last name with a horror director from that era). In They Live Carpenter used a few of his stock players (George "Buck" Flower and Keith David) and in the end he gets to do the self-referential thing when he has a bug-eyed alien TV commentator talking about movie violence and how it should be toned down ("people like George Romero and John Carpenter"). In The Fog, John really amps it up. He has a drifter named Nick Castle (writer of Escape from New York) a meteorologist named Dan O'Bannon (who went to film school with Carpenter), a sailor named Tommy Wallace (who's actually in the movie as a ghost), a doctor called Phibes, and in the cast is Jamie Lee Curtis, Tom Atkins, Adrienne Barbeau, "Buck" Flower, and one of his cinematographer's children. This was definitely a family affair for Carpenter and I think that goes some way toward explaining why it's so easy to watch.

On April 20th, a lot of spooky goings on...go....on....yeah, so between 12 and 1 in the morning a number of strange things take place in Antonio Bay, CA. After a car crashes, lights flicker, gas stations go haywire, Jamie Lee Curtis sleeps with Tom Atkins, and a priest finds his grandfather's diary behind a stone in his church's wall, DJ Stevie Wayne, proprietor of the only radio station on the small island of Antonio Bay, delivers her nightly shipping news. A fog bank is rolling in, boat captains beware. The crew of the Seagrass would have done good to heed that warning but by the time they get it in their heads to leave (When one of them says "I'm Drunk Enough" and then makes to stand up, I got to wondering what the hell goes on in Antonio Bay that the best thing three men can do with their night is to go out to sea and drink) the fog bank has already surrounded them. The men go out on deck in time to witness a rickety old ship pass them by. They might have written off to their drunk (I would) were it not for the musty pirates who murder them brutally a few seconds later.

The next day we get us some exposition. Jamie Lee and Tom's characters investigate the disappearance of the Seagrass. Tom is good friends with one of the sailors, you see. So when they find only one body covered in what looks like hundreds of years of sea debris, Tom is a little upset. When they bring the body back to shore for autopsy and all that good stuff, he wakes back up for a few seconds. Then Stevie's little boy Andy finds a piece of the Elizabeth Dane on the beach and gives it to her as a gift before she leaves for work, putting a babysitter in charge. And our last bit of business concerns Kathy Williams and Sandy Fadel. Kathy is the wife of one of the dead sailors and she's also the head of a committee preparing for the town's 100 year anniversary; Fadel is her secretary. What would really make the ceremony complete would be a benediction from the island's only priest. Well that priest, Father Malone is his generic name, discovers that a few hundred years ago, the town of Antonio Bay was founded by a crew of bastards. A boat called the Elizabeth Dane carrying a lot of gold and a lot of lepers was coming into town, but some malcontents who lived in the town, including Malone's grandfather, set a signal fire that drew the ship into some shoals and crashed it. This supernatural mischief seems a little weak when you consider that if its undead pirates out for revenge all they did was kill three people and mildly inconvenience some others. well real revenge is just around the corner. According to meteorologist Dan O'Bannon, the fog bank is rolling into town again, and this time it means business.

The Fog, as I said at the beginning is really quite easy to watch. That the film is framed as a campfire ghost story is fitting because it feels like one. Things happen for little to no reason other than they're spooky or because they're characteristic of ghost stories. Stevie Wayne's episode on top of her light house is a good example - they take forever to attack her, but it takes only seconds for them to dole out pain to the sailors aboard the seagrass. Because everyone of the performers has that sort of likable John Carpenter laconicism to them and so sympathy isn't impossible like it would be if this film were made by the Italians that The Fog takes its cues from. Frequently there are moments that feel overly drawn out like they do in Italian films. The murder scenes (and the illogicality of many of the supernatural occurrences) feel like they might have been taken from Suspiria or Anthropophagous. By 1981 or thereabouts everyone had had their turn at making a film like Suspiria - even Jesús Franco took a turn - and Carpenter's may be the best of them. The boldness of color, the way in which the arms of the undead pirates slowly plunge through walls, that Giorgio Moroder-esque score, the lingering over the murder weapon - if it weren't for Tom Atkins, I'd say this was an Italian Film. Carpenter had admitted as much, but I think he should rest easy knowing that his film makes much more sense and is ten times more fun than any of the cruel films he was aping. One look at his pirate zombies (which I guess to be fair aren't totally zombies, but they're zombies of a kind. Zombies with ghost-like tendancies) and you can tell what films he was watching. Rob Bottin did a really great job crafting the zombies and his performance as the lead pirate is really good. There's that one shot of the pirates standing in the church near the end - it may be his most beautifully composed framing of all his films. Intoxicatingly spooky is what I'd call it and the movie is worth watching just to give context to that shot.

It's funny how time makes you reconsider things - The Fog is by no means a great film, but when Carpenter financed a remake in 2006, the original looked like the superior, mature film. A remake can make anything look good, I guess. David Gordon Green's writing a remake of Suspiria; maybe that'll break the curse.

The film is full of sloppy compositional and editorial errors like this. It has more ADR than I can recall ever having seen in a big budget film like this; many of the film’s lines are shown coming from characters whose mouths are clearly not open. Many of the scenes cut out for theatrical release seem to have been dropped as part of a conscious effort to make the movie less interesting. Take the opening shots of Charles Dance’s Clemens walking alone on the beach in his enormous coat. It’s a masterfully composed sequence and adds so much to his character without even a word of dialogue and the producers tossed it in favor of a quicker, cheaper opening. Then there’s the dog alien vs. the ox alien. The dog makes more sense anatomically and behaviorally, but the feasibility of an ox on the planet is greater. And why does no one but Dillon seem to exhibit any sort of religious fervor? What happens to Eric during the climax? Why not make more of the prisoner’s belief that the alien has brought the apocalypse? That could have been so much more compelling than watching everyone bicker for acts 2 and 3. It also would have given the religious aspects of the movie some reason for existing, cause as it stands it accomplishes next to nothing. Why bother giving Clemens as much exposition as he gets if he’s going to be killed for no real reason? Why spend so much time with Aaron and Ripley as they go round and round and round? The film was filled with so many aborted ideas and so many half-cooked ones that it feels like you’ve eaten an entire meal of bread and water because your dinner never arrived.

The film is full of sloppy compositional and editorial errors like this. It has more ADR than I can recall ever having seen in a big budget film like this; many of the film’s lines are shown coming from characters whose mouths are clearly not open. Many of the scenes cut out for theatrical release seem to have been dropped as part of a conscious effort to make the movie less interesting. Take the opening shots of Charles Dance’s Clemens walking alone on the beach in his enormous coat. It’s a masterfully composed sequence and adds so much to his character without even a word of dialogue and the producers tossed it in favor of a quicker, cheaper opening. Then there’s the dog alien vs. the ox alien. The dog makes more sense anatomically and behaviorally, but the feasibility of an ox on the planet is greater. And why does no one but Dillon seem to exhibit any sort of religious fervor? What happens to Eric during the climax? Why not make more of the prisoner’s belief that the alien has brought the apocalypse? That could have been so much more compelling than watching everyone bicker for acts 2 and 3. It also would have given the religious aspects of the movie some reason for existing, cause as it stands it accomplishes next to nothing. Why bother giving Clemens as much exposition as he gets if he’s going to be killed for no real reason? Why spend so much time with Aaron and Ripley as they go round and round and round? The film was filled with so many aborted ideas and so many half-cooked ones that it feels like you’ve eaten an entire meal of bread and water because your dinner never arrived.