Eaten Alive

by Tobe Hooper

Classifiction: Raperevengicus Crocodsadagingstarae

Something is rotten in the state of Texas. After a prostitute who is clearly a newbie shies away from john Robert Englund’s demand for sodomy, she heads into the bayou looking for a place to stay (incidentally, his opening lines, paraphrase “I’m Buck and my favored activity with women rhymes with my name” was lifted by Quentin Tarentino for his film Kill Bill!). She finds the Starlight motel run by cracked war veteran Judd. Judd seems harmless enough, if clearly off-balance, until he deduces that our girl is a prostitute, or was one at any rate. So upset is Judd that he strips her shirt off her, beats her, stabs her with a pitchfork, and feeds her to his pet Crocodile. Thank god we got somewhere; with Robert Englund’s randy hillbilly routine and the endless prowling about that our girl does this film was starting to look like a backwoods porn movie.

Something is rotten in the state of Texas. After a prostitute who is clearly a newbie shies away from john Robert Englund’s demand for sodomy, she heads into the bayou looking for a place to stay (incidentally, his opening lines, paraphrase “I’m Buck and my favored activity with women rhymes with my name” was lifted by Quentin Tarentino for his film Kill Bill!). She finds the Starlight motel run by cracked war veteran Judd. Judd seems harmless enough, if clearly off-balance, until he deduces that our girl is a prostitute, or was one at any rate. So upset is Judd that he strips her shirt off her, beats her, stabs her with a pitchfork, and feeds her to his pet Crocodile. Thank god we got somewhere; with Robert Englund’s randy hillbilly routine and the endless prowling about that our girl does this film was starting to look like a backwoods porn movie.Well, as we connoisseurs of revenge films know, that poor one-time whore’s brother or father is bound to show up. Before said vengeful spirits show up, one the screen’s most crooked family shows up looking to spend the night. Faye, Roy, and Angie stop in…for directions if my interpretation of this batshit craziness is correct, but things take a turn for the bizarre when Angie’s dog Snoopy winds up in the croc’s jaws. What happens next is a little hazy; Faye takes Angie upstairs and Roy follows, Angie understandably upset, and then Roy starts flipping out too. Faye takes some pills and then takes her wig off (…?) and starts berating Roy. Best I can figure, they’re criminals, but Angie is Faye’s daughter. Anyway, Roy starts barking like the dog and then goes downstairs to shoot the crocodile with the shotgun they’ve had in the trunk the whole time, with Judd trying to talk him down the whole time. When talking fails, Judd takes a scythe to his opponents chest and then the gator clamps down on his shoulder. Then Judd ties Faye to the bed and chases Angie under his porch; they’ll both spend the rest of the movie in their respective places. How do we know this, because Hooper and his editor show them there every five minutes, even though their situation almost never changes.

Then Mel Ferrer and a blonde show up to move the damn plot along. Mel is the prostitute from the prologue’s father and the blonde her sister. They’ve come looking for our victimess and Mel gets a scythe in the throat for his troubles (he holds it in place for like 3 minutes to make sure Hooper's camera doesn’t miss it). Then we take a detour to the local watering hole where Robert Englund picks up another girl and brings her to the starlight; this takes entirely too long. Especially because it ends with Englund in the gator’s mouth instead of as the film’s hero. The prostitute gets away from Judd and then our two remaining female characters get the revenge we knew was coming from the start of this sleazy picture. When people discuss the origins of the slasher film, I don’t get why they don’t include this in the discourse. A creepy guy who kills the promiscuous with a scythe...sound like the 80s in a nutshell to anyone else? It is also, best I can tell, the first movie that used a crocodilian as a horror device independent of the odd mad scientist or eccentric billionaire; it even gets it’s own stalker moment. In fact the only scary part of the film occurs when the croc goes after Angie under the porch.

Then Mel Ferrer and a blonde show up to move the damn plot along. Mel is the prostitute from the prologue’s father and the blonde her sister. They’ve come looking for our victimess and Mel gets a scythe in the throat for his troubles (he holds it in place for like 3 minutes to make sure Hooper's camera doesn’t miss it). Then we take a detour to the local watering hole where Robert Englund picks up another girl and brings her to the starlight; this takes entirely too long. Especially because it ends with Englund in the gator’s mouth instead of as the film’s hero. The prostitute gets away from Judd and then our two remaining female characters get the revenge we knew was coming from the start of this sleazy picture. When people discuss the origins of the slasher film, I don’t get why they don’t include this in the discourse. A creepy guy who kills the promiscuous with a scythe...sound like the 80s in a nutshell to anyone else? It is also, best I can tell, the first movie that used a crocodilian as a horror device independent of the odd mad scientist or eccentric billionaire; it even gets it’s own stalker moment. In fact the only scary part of the film occurs when the croc goes after Angie under the porch.Tobe Hooper was in a tight spot after The Texas Chainsaw Massacre; sure he’d just made one of the 8 or 9 most effective horror films ever, but he was in absolutely no position to celebrate. The movie’s rights went to the mafia-front production company that backed it and Hooper, writer Kim Henkle and co. didn’t see a dime. Today if Tobe Hooper had made a film as effective as Texas Chainsaw he’d have two sequels offered, a blank check for his next project and a remake in the works. Back then he incited a fervor that left him utterly offerless. Italians ripped off the film, but didn’t realize they could have scooped Hooper up and had him making Giallos that next year if they’d just asked. So instead Hooper went untouched for two years after until Eaten Alive and its lousy script showed up. Naturally he bit because filmmaking isn’t something a director can cure himself of and to be fair he and Henkle turn what was ultimately an excuse to see Roberta Colins, Crystin Sinclaire, and Betty Cole with their shirts off into a truly unnerving film. He and Henkel decided to base their throw-away bayou murder story on Joe Ball, a bar-owner who fed prostitutes to the crocodile he used to drum up business. Eaten Alive shows Hooper’s interest in creepy serial killers evolving slightly; we spend most of the film’s running time with the killer rather than the heroes, a trap that would lead Hooper into a good deal of trouble when it came time to make Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, a movie even more ill-advised than this one.

But I guess, here, why not? Neville Brand is about as creepy a bastard as showed up in American horror in the 70s and his turn as a fascistic, shell-shocked lunatic is a worthy successor to Leatherface and his family (as my dad pointed out, he looks like an older version of the Hitchhiker if he hadn’t been pancaked by a truck at Chainsaw’s end). He works, Robert Englund works, Mel Ferrer, well, he didn’t have much to cheer about, but he doesn’t embarrass himself as bad as Arthur Kennedy does in Taboo Island or Let Sleeping Corpses Lie. Marilyn Burns surprised me because I didn’t recognize her until the end when, oddly enough, she’s screaming and crying just like Sally Hardesty but she makes a decent showing of herself. Ultimately, the film is vile and wastes way too much time (it’s 89 minutes feel like 140) and works, like so many late 70s video nasties do, mostly as a curio; it’s a veritable museum of the washed-up never-was: Carolyn Jones, Mel Ferrer, Neville Brand, and Stuart Whitman almost give the cast of Tentacles a run for their money as falling stars go. It’s certainly a more interesting film than say, Tenebre or Don’t Torture A Duckling, but even someone with as big an urge to create as Tobe Hooper can’t hide the fact that the starlight motel is a soundstage, that his croc’s made of rubber, and that he’s making a slasher film. I dare anyone to make a worse rubber crocodile than…

But I guess, here, why not? Neville Brand is about as creepy a bastard as showed up in American horror in the 70s and his turn as a fascistic, shell-shocked lunatic is a worthy successor to Leatherface and his family (as my dad pointed out, he looks like an older version of the Hitchhiker if he hadn’t been pancaked by a truck at Chainsaw’s end). He works, Robert Englund works, Mel Ferrer, well, he didn’t have much to cheer about, but he doesn’t embarrass himself as bad as Arthur Kennedy does in Taboo Island or Let Sleeping Corpses Lie. Marilyn Burns surprised me because I didn’t recognize her until the end when, oddly enough, she’s screaming and crying just like Sally Hardesty but she makes a decent showing of herself. Ultimately, the film is vile and wastes way too much time (it’s 89 minutes feel like 140) and works, like so many late 70s video nasties do, mostly as a curio; it’s a veritable museum of the washed-up never-was: Carolyn Jones, Mel Ferrer, Neville Brand, and Stuart Whitman almost give the cast of Tentacles a run for their money as falling stars go. It’s certainly a more interesting film than say, Tenebre or Don’t Torture A Duckling, but even someone with as big an urge to create as Tobe Hooper can’t hide the fact that the starlight motel is a soundstage, that his croc’s made of rubber, and that he’s making a slasher film. I dare anyone to make a worse rubber crocodile than…The Big Alligator River

by Sergio Martino

Classification: Jawsripofficus Xenophobodilidae

…rest easy, Tobe, Sergio Martino’s got you licked in the rubber crocodile department.

…rest easy, Tobe, Sergio Martino’s got you licked in the rubber crocodile department.Ok, so, remember how I said Jaws was the film that gave us the majority of our crocodile films, well here’s how that works. So, after Jaws came out, it sparked a remake/rip-off frenzy the likes of which can really only be compared to Dawn of the Dead. One of the later attempts at Jaws-like success while the iron was still relatively hot, Big Alligator River, is by no means a good film, but I give it credit for three things: two of the most likeable protagonists in Italian movie history, inspiring the next few big croc movies and featuring a decent croc head.

Let’s meet those protagonists and then I’ll get to point two. Daniel Nessel (what nationality is that name supposed to be? French, maybe?) is a photographer who, along with model Sheena, has just been hired by eccentric billionaire Mel Ferrer (AGAIN?! HAVE YOU LEARNED NOTHING ABOUT DIGNITY, MAN?) to take promotional photographs for his latest brilliant idea. Our evil capitalist had an epiphany, he’s built a theme park and resort in the middle of the jungle called The Paradise. Guess what the theme is? The Jungle! Stunning! So wildlife and a superstitious native tribe aren’t obstacles, they're amusements! How progressive. It doesn’t take long for Mel’s biggest problem to rear it’s scaly head. One night Sheena takes a boytoy out on the lake and the two of them get the bite and their boat washes up the next day.

Not coincidentally, when the boat comes ashore, the natives don’t; not a one of them shows up for work the next day. Mel could give a goddamn, but Allie, the Paradise’s liaison with the natives, hears him out and the two take off down the river to see what has the native’s spooked. Allie and Dan find a crazed missionary who’s carved a giant crocodile head out of stone in a cave (wonder what that’s all about). Also turns out that the natives worship said crocodile and they believe they’re being punished for fraternizing with whites. Dan tries to hit the other white folks with some knowledge, but is Mel having that? Well, if Dan’s our Sheriff Brody, I guess that makes Mel our Mayor, don’t it? So, we know the answer as well as we know that the party-on-a-raft that Mel takes to the water is about to get interrupted by a big crocodile and his bath-toy double. And let’s throw in some angry natives with flaming arrows for good measure.

Not coincidentally, when the boat comes ashore, the natives don’t; not a one of them shows up for work the next day. Mel could give a goddamn, but Allie, the Paradise’s liaison with the natives, hears him out and the two take off down the river to see what has the native’s spooked. Allie and Dan find a crazed missionary who’s carved a giant crocodile head out of stone in a cave (wonder what that’s all about). Also turns out that the natives worship said crocodile and they believe they’re being punished for fraternizing with whites. Dan tries to hit the other white folks with some knowledge, but is Mel having that? Well, if Dan’s our Sheriff Brody, I guess that makes Mel our Mayor, don’t it? So, we know the answer as well as we know that the party-on-a-raft that Mel takes to the water is about to get interrupted by a big crocodile and his bath-toy double. And let’s throw in some angry natives with flaming arrows for good measure. The Big Alligator River is a mess, alright, and it’s flaws are nearly endless, and it’s been really well preserved, which make its shortcomings especially glaring. On the plus side we have Claudio Cassinelli and Barbara Bach who I like more than any other Italian horror heroes for reasons I can’t explain; maybe because they remain respectful of the natives that everyone, including Sergio Martino, holds in contempt. Then there’s the head of the Croc which comes close to looking as convincing as the big shark head in Jaws (the "gonna need a bigger boat" moments in this film are almost as convincing). Given this film’s budget and it’s 1979 release date, that’s quite a feat indeed. That illusion is shattered when, more than once, we are pulled out of a nocturnal hunting trip to be shown what couldn’t be any more clearly a day-time shot of a croc-shaped plastic toy floating clumsily in a pool. At no time does the body of the crocodile look like anything but a child’s play-thing; the croc even bobs like a toy in the ‘waves’. With competition like that, Mel got off easy in the embarrassment department - when he gets struck with a flaming arrow, he almost looks relieved. No one’s performance is great, in fact the only thing that works the way it should is Martino’s slow-motion shots and this film’s function as a Jaws rip-off. There’s even a Brody-in-the-sinking-boat scene followed by a climax that wants to one-up Spielberg, but simply can’t. Well, at least there’s no nudity.

The Big Alligator River is a mess, alright, and it’s flaws are nearly endless, and it’s been really well preserved, which make its shortcomings especially glaring. On the plus side we have Claudio Cassinelli and Barbara Bach who I like more than any other Italian horror heroes for reasons I can’t explain; maybe because they remain respectful of the natives that everyone, including Sergio Martino, holds in contempt. Then there’s the head of the Croc which comes close to looking as convincing as the big shark head in Jaws (the "gonna need a bigger boat" moments in this film are almost as convincing). Given this film’s budget and it’s 1979 release date, that’s quite a feat indeed. That illusion is shattered when, more than once, we are pulled out of a nocturnal hunting trip to be shown what couldn’t be any more clearly a day-time shot of a croc-shaped plastic toy floating clumsily in a pool. At no time does the body of the crocodile look like anything but a child’s play-thing; the croc even bobs like a toy in the ‘waves’. With competition like that, Mel got off easy in the embarrassment department - when he gets struck with a flaming arrow, he almost looks relieved. No one’s performance is great, in fact the only thing that works the way it should is Martino’s slow-motion shots and this film’s function as a Jaws rip-off. There’s even a Brody-in-the-sinking-boat scene followed by a climax that wants to one-up Spielberg, but simply can’t. Well, at least there’s no nudity.Alligator

by Lewis Teague

Classification: Jawsripofficus AlligaBlandheroae

Well, as Sergio Martino could tell you, Big Alligator fared well at the box office. It was the last of his films, and one of the last Italian horror films, to really bank here in the States. It stands to reason; Americans liked Jaws, so why wouldn’t they come out to see the same trick with a crocodile. Well apparently Americans saw the same logic. So producers set about ripping off a ripoff while lessening the impact of both its predessecors by changing the setting, cheapening the protagonists, and loading it with more clichés than a gillman film (which Sergio Martino made, actually). How wonderfully incestuous.

Well, as Sergio Martino could tell you, Big Alligator fared well at the box office. It was the last of his films, and one of the last Italian horror films, to really bank here in the States. It stands to reason; Americans liked Jaws, so why wouldn’t they come out to see the same trick with a crocodile. Well apparently Americans saw the same logic. So producers set about ripping off a ripoff while lessening the impact of both its predessecors by changing the setting, cheapening the protagonists, and loading it with more clichés than a gillman film (which Sergio Martino made, actually). How wonderfully incestuous.Our story begins with a public service; don’t rage at your children, talk to them. After a tiff, an angry mother flushes her daughter Marissa’s tiny petshop alligator down the toilet. Twenty or so years later, we meet our hero. Robert Forster is David Madison, a cop famous for getting his partner killed. When he gets sent to the sewer with a rookie to look for a missing sanitation worker, the new guy gets a chest full of giant alligator teeth. Needless to say, Madison’s reputation doesn’t improve, but he does catch the attention of Marissa Kendall, who thinks she might know what killed the rookie. An evil corporation has been flushing lab animals stuffed with growth hormones into the sewer and Marissa feels more than a little compelled to stop them and the gator; as you may have guessed, the large beastie roaming the streets was her one-time childhood pet. The plot from here is basically one stalk-and-kill after another, the most impressive of which happens at a wedding that our villain happens to be present for. Thanks to pretty impressive miniatures and real gator footage, our boy looks real, but that's not enough to save this movie.

When I was in, I want to say 4th grade, I got into horror in a big way. I had already seen a number of horror films (John Carpenter’s The Thing being the conquest I had the most pride in being able to endure) but my obsession began in earnest thanks largely to a movie called Terror in the Aisles. Terror isn’t a horror film, but a collection of snippets from several dozen of them. Of these clips were segments of films like Texas Chainsaw, Rosemary’s Baby, Alien, and Alligator. I made it my mission to seek out the few films whose segments seemed the most interesting (keep my age in mind). So, I went to the little VHS rental place on the empty side of town with my parents and among dusty laserdisc copies of Freejack I saw the horror films that Blockbuster didn’t carry. Alligator and Texas Chainsaw, the two films I pined for the most, were not what I expected them to be. Texas Chainsaw I admit I didn’t understand until roughly three years later but Alligator just plain left me cold. With the exception of a scene where a child is eaten in a swimming pool, all the allure of the few seconds I’d seen in Terror in the Aisles had vanished. A big alligator in 1980 could only move as fast as the robotics team made it after all. This would all change in a few years, but for now, what I had was Robert Forster as an unlikeable prig and a cast of even more forgettable characters doing battle with a gator that spent half of it’s time being just a regular sized animal hanging out waiting for the editor to make him eat someone. The wedding scene, where our scaly friend finally takes some decisive action and crushes the limousine of the villain was and still is kind of fun, but it’s a little less fun now that I’ve seen some of today’s gator films. In fact most creature films turned to nostalgia after the admittedly bad Deep Blue Sea (yeah, it sucked, but name one American-produced creature feature that had miniatures after this film). Computers changed everything alright, but they can’t change bad acting and listless direction.

When I was in, I want to say 4th grade, I got into horror in a big way. I had already seen a number of horror films (John Carpenter’s The Thing being the conquest I had the most pride in being able to endure) but my obsession began in earnest thanks largely to a movie called Terror in the Aisles. Terror isn’t a horror film, but a collection of snippets from several dozen of them. Of these clips were segments of films like Texas Chainsaw, Rosemary’s Baby, Alien, and Alligator. I made it my mission to seek out the few films whose segments seemed the most interesting (keep my age in mind). So, I went to the little VHS rental place on the empty side of town with my parents and among dusty laserdisc copies of Freejack I saw the horror films that Blockbuster didn’t carry. Alligator and Texas Chainsaw, the two films I pined for the most, were not what I expected them to be. Texas Chainsaw I admit I didn’t understand until roughly three years later but Alligator just plain left me cold. With the exception of a scene where a child is eaten in a swimming pool, all the allure of the few seconds I’d seen in Terror in the Aisles had vanished. A big alligator in 1980 could only move as fast as the robotics team made it after all. This would all change in a few years, but for now, what I had was Robert Forster as an unlikeable prig and a cast of even more forgettable characters doing battle with a gator that spent half of it’s time being just a regular sized animal hanging out waiting for the editor to make him eat someone. The wedding scene, where our scaly friend finally takes some decisive action and crushes the limousine of the villain was and still is kind of fun, but it’s a little less fun now that I’ve seen some of today’s gator films. In fact most creature films turned to nostalgia after the admittedly bad Deep Blue Sea (yeah, it sucked, but name one American-produced creature feature that had miniatures after this film). Computers changed everything alright, but they can’t change bad acting and listless direction.Alligator was doomed from the start. Frank Ray Perelli pitched the movie as something like Redneck Zombies meets Jaws. His producers knew this was as good an idea as a root canal themepark ride, and so they hired writer number 2 to salvage their Jaws ripoff from this fool’s pen. John Sayles was a name to small production houses because he’d written the semi-successful Roger Corman-produced Pirana, a Jaws ripoff in its own right. Mark L. Rosen, who would learn a thing or two about plagiarizing when Michael Bay’s The Island was released, and the other producers hired John Sayles. Sayles had a brain in his head and thought Perelli’s idea for beer fueling a mutant alligator was….well pretty fucking stupid. Sayles’ horror films, conscious and reasonable though they are, never account for lackluster direction, which is all it takes to make them boring. Joe Dante’s handling of The Howling is a good example. Joe can do a stalking scene with the best of them, but some of his acting-under-stress scenes don’t measure up; I digress (I love The Howling, by the way). We’re here for big teeth of another kind, which didn’t make much of an improvement throughout the 80s and 90s.

The gator film got a few entries, like Australia’s Dark Age, which maybe a hundred living people have seen. It wasn’t until computer generated effects reached their apex in the 90s that we got a glimpse of how good Alligators could be.

The gator film got a few entries, like Australia’s Dark Age, which maybe a hundred living people have seen. It wasn’t until computer generated effects reached their apex in the 90s that we got a glimpse of how good Alligators could be.Lake Placid

by Steve Miner

Classification: Crocodynamation Pettybickerous

When you realize that this film was written by David E. Kelly, it starts to makes a lot of sense. Kelly was the writer/creator of many a maudlin TV drama, including Boston Public. I find this incredibly apt as the only catastrophe that never occurred in the fictitious high school of Boston Public was the appearance of an unexplained 30-foot Crocodile. Said Croc isn’t in a high school, but a lake in Maine and his appearance has confounded paleontologist Bridget Fonda, fish-and-game warden Bill Pullman, sheriff Brendan Gleeson (28 Days Later was a real break for Brendan), and nature-y asshole Oliver Platt. They bicker and fumble around with what might be killing people until the beast makes an appearance and puts their suspicions to bed. They grill the old lady who lives on the lake, Betty White, the best thing about this movie other than the giant crocodile, and it turns out she’s been feeding it for a while now. Oliver Platt and Bridget Fonda are obnoxious and soft in all the wrong areas and decide killing it would be wrong and coax the others into trying to catch it in an elaborate trap. This doesn’t go quite as they would like it to, but it doesn’t go nearly as awry as it should.

When you realize that this film was written by David E. Kelly, it starts to makes a lot of sense. Kelly was the writer/creator of many a maudlin TV drama, including Boston Public. I find this incredibly apt as the only catastrophe that never occurred in the fictitious high school of Boston Public was the appearance of an unexplained 30-foot Crocodile. Said Croc isn’t in a high school, but a lake in Maine and his appearance has confounded paleontologist Bridget Fonda, fish-and-game warden Bill Pullman, sheriff Brendan Gleeson (28 Days Later was a real break for Brendan), and nature-y asshole Oliver Platt. They bicker and fumble around with what might be killing people until the beast makes an appearance and puts their suspicions to bed. They grill the old lady who lives on the lake, Betty White, the best thing about this movie other than the giant crocodile, and it turns out she’s been feeding it for a while now. Oliver Platt and Bridget Fonda are obnoxious and soft in all the wrong areas and decide killing it would be wrong and coax the others into trying to catch it in an elaborate trap. This doesn’t go quite as they would like it to, but it doesn’t go nearly as awry as it should.The name Steve Miner in any film is never a good sign. Other than tarnishing George Romero’s scariest film with his pitifully stupid and immature remake, Miner’s other credits include Friday the 13th II & III, House, Warlock, and more bad TV than any self-respecting director could ever sleep soundly with. Lake Placid could be said to illustrate his style perfectly; people argue, get nowhere, act childishly, and then there’s one effective scare scene. Combine that with Kelly’s television-worthy script and you have an hour and a half of childish fun. Sort of like in any episode of House, it’s fun to watch people argue separated by bits of intensity, but this isn’t the film I wanted when I started seeing previews and getting my hopes up. I had been disappointed pretty heavily by Alligator and had long waited for the film that was going to really make a showing for the order giant gator film. Lake Placid features a pretty convincing CG monster in a decade full of pretty miserable ones but Miner has no idea how to handle him. When Bridget Fonda finds herself alone in the lake with our monster croc, we have the film’s one good scene in a film full of missed oppurtunities. And of course because David E. Kelly wrote it, there’s no real tension. Anyway, it was one of the better CG animals of its time and in many respects hasn’t been outdone, at least as crocodilians are concerned.

Lake Placid is fun and it doesn’t totally suck, it just isn’t scary. It also has a few major points against it in that it, like Jaws before it, inspired many bad knock-offs. One of them by the one man who should know better than to delve into an order he doesn’t have the cash or crew to pull off (hint: It’s not Sergio Martino)

Lake Placid is fun and it doesn’t totally suck, it just isn’t scary. It also has a few major points against it in that it, like Jaws before it, inspired many bad knock-offs. One of them by the one man who should know better than to delve into an order he doesn’t have the cash or crew to pull off (hint: It’s not Sergio Martino)Crocodile

by Tobe Hooper

Classification: Madefortvidae Shouldhaveknownbetterus

I can forgive a lot; Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, for example. It was terrible, but Tobe Hooper needed money and he paid for his mistake with more than a decade of shitty jobs. I can forgive Spielberg’s family-friendly instinscts overriding Hooper's on the set of Poltergeist. And I can forgive Eaten Alive because he needed to direct a movie and he needed money and I'm sure Eaten Alive sounded better with a bigger budget behind it. I don’t know that I can forgive a made-for-sci-fi teen sex movie that makes Eaten Alive look like Psycho. I caught this movie during a rash of terrible creature movies made for the Sci-Fi channel back when it was still in its infancy. Though Crocodile is better than Octopus or Python or Spiders it still isn't great. In fact that the movie Komodo is much better than this is not encouraging; when your movie isn't the best of a crop of made-for-sci-fi monster films I think some soul-searching is called for.

I can forgive a lot; Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, for example. It was terrible, but Tobe Hooper needed money and he paid for his mistake with more than a decade of shitty jobs. I can forgive Spielberg’s family-friendly instinscts overriding Hooper's on the set of Poltergeist. And I can forgive Eaten Alive because he needed to direct a movie and he needed money and I'm sure Eaten Alive sounded better with a bigger budget behind it. I don’t know that I can forgive a made-for-sci-fi teen sex movie that makes Eaten Alive look like Psycho. I caught this movie during a rash of terrible creature movies made for the Sci-Fi channel back when it was still in its infancy. Though Crocodile is better than Octopus or Python or Spiders it still isn't great. In fact that the movie Komodo is much better than this is not encouraging; when your movie isn't the best of a crop of made-for-sci-fi monster films I think some soul-searching is called for.Open on two dumbass fisherman whose idea of fun is smashing crocodile eggs. Mama croc shows up and eats them both rightly. Next we meet 8 completely unlikable twenty somethings. Their names aren’t important in the least except that the more silly their name sounds the quicker they’ll get killed - actually their listing on the IMDB is in the order that they get killed. Anyway, Mama Croc is angry about her eggs being smashed and takes it out on the kids, plus the circus freak who imported the croc in the first place and the sheriff. Reasons for watching: 0. Yeesh, Salem's Lot this is not! Because Tobe Hooper is at the helm, the acting isn’t terrible, the effects are alright, and there are a few jump-shocks but this is just not a good movie. This is still about stupid almost-teenagers and the way the croc is outsmarted is so fucking stupid it belittles everyone’s intelligence, Hooper’s most of all. It isn’t funny-bad, it’s just bad.

The hits keep on rolling.

The hits keep on rolling.Blood Surf

by James D.R. Hickox

Classification: Frontprojecticus Crocoshitidae

In reviewing for my gator-centric holiday revue, I found a pretty good summation of this South African indie on IMDB in the user quote section.

“Hey, I've found it - The worst horror film of all time.”

I hope you like unnatractive women showing their tits! Cause that's why this film got made. You know when directors try to make sports seem extreme and it never works. Welcome to Blood Surfing, the sport where surfers cut themselves to excite sharks. Well these fucking rejects don’t get eaten by sharks, but by a big front-projected puppet crocodile. And the girls take their shirts off. As vile as Swordfish, as stupid as Hellgate. The conclusion is something to behold; watch it if you’ve never seen a 2D animated crocodile fly. And yet, rock bottom hasn’t yet arrived. For all this film’s problems, of which it is entirely composed, it was an independent film. Guess what was produced by a guy who’d been making movies for 40 years?

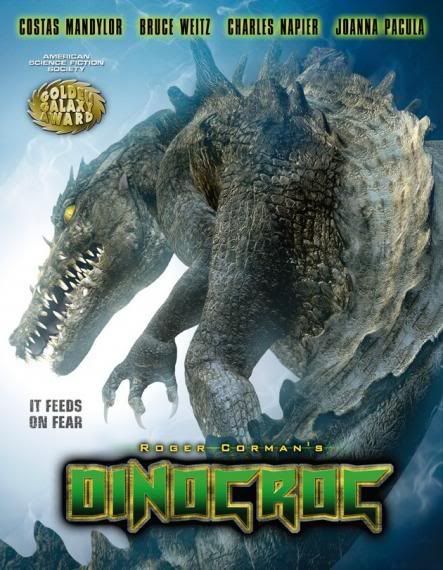

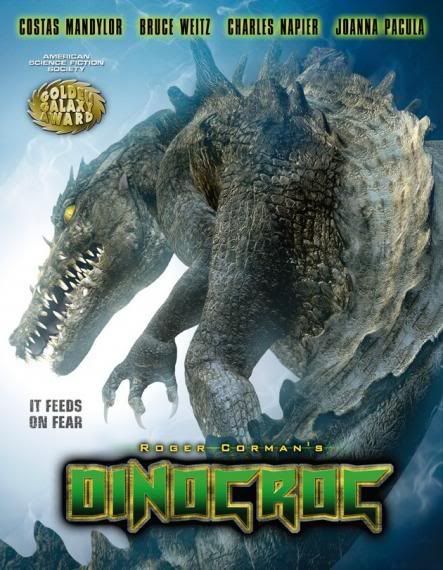

Dinocroc

by Kevin O’Neill

Classification: Areyoufuckingserious Rogercormanae

I’m just joking, I didn’t sit through this piece of shit, but I did see the last ten minutes on sci-fi. I just thought I’d point out that Roger Corman, the man who’s been around long enough to produce both Death Race 2000 and it’s remake couldn’t recognize that Dinocroc was a stupid idea. Ok, back to real movies for a second. In the years between Eaten Alive and our next film, money was made. Enough money that someone somewhere thought that Alligator, Lake Placid, and Crocodile all warranted sequels, all of which, mind you, I saw. A few weeks ago I was made aware of a phenomenon which floored me, but not before I subjected myself to another filmic atrocity in the Steve Miner school of filmmaking.

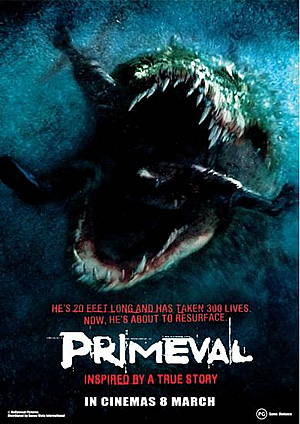

Primeval

Primeval

by Michael Katleman

Classification: Crueltoallofus Crocodeservetodie

by Kevin O’Neill

Classification: Areyoufuckingserious Rogercormanae

I’m just joking, I didn’t sit through this piece of shit, but I did see the last ten minutes on sci-fi. I just thought I’d point out that Roger Corman, the man who’s been around long enough to produce both Death Race 2000 and it’s remake couldn’t recognize that Dinocroc was a stupid idea. Ok, back to real movies for a second. In the years between Eaten Alive and our next film, money was made. Enough money that someone somewhere thought that Alligator, Lake Placid, and Crocodile all warranted sequels, all of which, mind you, I saw. A few weeks ago I was made aware of a phenomenon which floored me, but not before I subjected myself to another filmic atrocity in the Steve Miner school of filmmaking.

Primeval

Primevalby Michael Katleman

Classification: Crueltoallofus Crocodeservetodie

This one claims to be more than just a post-Lake Placid gore fest, cause it’s framing story has to do with a corrupt African government. I don’t personally get why they bothered because for all the awareness they try to raise about corruption and genocide and all that, they undo it by making Orlando Jones act like a complete dipshit from reel 1 to reel infinity. His token black guy schtick is old before you’ve fully grasped what’s going on in the plot. Anyway, our story opens on a big goddamn crocodile that the natives have nicknamed ‘Gustave’. His latest meal was a UN peacekeeper which has gotten the US’s attention. Aviva Masters, a puff-piece reporter for a fake news network, wants to go to Africa to catch it, which she admits is a slightly loaded decision; going to Burundi to catch a crocodile puts them in harm’s way in two big ways. Burundi, as anyone can tell you, isn’t exactly Reading, Massachusets, and the section Masters wants to head into is run by a dictator the natives nicknamed ‘Little Gustave’ because he’s killed just as many people as his scaly namesake. In order to get the story done proper she cons shamed journalist Tim Manfrey and his cameraman Steven (Orlando Jones) to come with him (he just fucked up some important thing with a senator and looks like a jackass so he has to do it to remain unfired). Manfrey may also help Masters get out of bogus-journalism hell and move into the big times. Masters has also arranged to bring along Matthew Collins, a standoffish Australian television wildlife expert. So they arrive, meet their liaison ‘Harry’ who sends them to find a trapper called Krieg (Jurgen Prochnow, who really must be feeling the sting of hasbeendom). Krieg and Collins are immediately at odds because Krieg does very little to cover up the fact that he wants the big croc dead; Collins, being of the Lake Placid school of tree-hugger, doesn’t want any harm to come to the gator. Allow me to clarify my snide comments; I’m not in favor of harming animals and have for a short while now been a vegetarian, but what gets me wound up is when people find themselves in situations that are ultimately going to lead to a lot of people dying and still insist that a big man-eating creature deserves the same care that a small pet does. This is nonsense and I don’t know any animal lover who would get up in arms when people start getting eaten by the dozen. Anyway, so amidst the predicatably ineffective attempts to capture our gator, Steven and his camera happen to witness an execution by some of Little Gustave’s hired guns. Also predictably Little Gustave has men planted in the expedition who find out what Steven has seen and agree that another execution is in order. They manage to escape but do so without weapons or a boat; 10 to 1 this is going to really well. Any takers? Much biting and shooting ensues, but not nearly enough and not nearly in time.

This one claims to be more than just a post-Lake Placid gore fest, cause it’s framing story has to do with a corrupt African government. I don’t personally get why they bothered because for all the awareness they try to raise about corruption and genocide and all that, they undo it by making Orlando Jones act like a complete dipshit from reel 1 to reel infinity. His token black guy schtick is old before you’ve fully grasped what’s going on in the plot. Anyway, our story opens on a big goddamn crocodile that the natives have nicknamed ‘Gustave’. His latest meal was a UN peacekeeper which has gotten the US’s attention. Aviva Masters, a puff-piece reporter for a fake news network, wants to go to Africa to catch it, which she admits is a slightly loaded decision; going to Burundi to catch a crocodile puts them in harm’s way in two big ways. Burundi, as anyone can tell you, isn’t exactly Reading, Massachusets, and the section Masters wants to head into is run by a dictator the natives nicknamed ‘Little Gustave’ because he’s killed just as many people as his scaly namesake. In order to get the story done proper she cons shamed journalist Tim Manfrey and his cameraman Steven (Orlando Jones) to come with him (he just fucked up some important thing with a senator and looks like a jackass so he has to do it to remain unfired). Manfrey may also help Masters get out of bogus-journalism hell and move into the big times. Masters has also arranged to bring along Matthew Collins, a standoffish Australian television wildlife expert. So they arrive, meet their liaison ‘Harry’ who sends them to find a trapper called Krieg (Jurgen Prochnow, who really must be feeling the sting of hasbeendom). Krieg and Collins are immediately at odds because Krieg does very little to cover up the fact that he wants the big croc dead; Collins, being of the Lake Placid school of tree-hugger, doesn’t want any harm to come to the gator. Allow me to clarify my snide comments; I’m not in favor of harming animals and have for a short while now been a vegetarian, but what gets me wound up is when people find themselves in situations that are ultimately going to lead to a lot of people dying and still insist that a big man-eating creature deserves the same care that a small pet does. This is nonsense and I don’t know any animal lover who would get up in arms when people start getting eaten by the dozen. Anyway, so amidst the predicatably ineffective attempts to capture our gator, Steven and his camera happen to witness an execution by some of Little Gustave’s hired guns. Also predictably Little Gustave has men planted in the expedition who find out what Steven has seen and agree that another execution is in order. They manage to escape but do so without weapons or a boat; 10 to 1 this is going to really well. Any takers? Much biting and shooting ensues, but not nearly enough and not nearly in time.Primeval is really dumb. Really, REALLY dumb. The only thing reasonably well planned is the framing story, but then things get stupid and lazy. The people are all so odious, not to mention just plain hard to look at, that I could have cared less what happened to any of them. By the time the killing starts, no death could be gruesome enough to give them all what they deserve. Admittedly the croc’s decent, but considering it’s been ten years since Lake Placid, not nearly good enough. There’s one scene that I had to begrudgingly admit looked really cool, when our gator first shows his whole body when he attacks the trapper’s cage with a young boy inside it. A silhouetted gator the size of a school bus crawling on a big cage in the moonlight is the reason to watch creature films in the first place and I’d forgive the rest of the film if it weren’t so goddamned offensive and not just offensive in its portrayal of non-whites. That’s bad, sure, but I mean the little things. You know a movie doesn’t have a proper budget when a ‘war lord’ sends three guys after the protagonists, not the whole army he’s supposed to have at his command. At no point does the reputation of Little Gustave ever seem more believable than Orlando Jones’ character. Also, correct me if I’m wrong, but crocs don’t go out of their way to chase after prey; they sit and wait for gazelles in the river, mostly. Gustave spends much of this film sprinting after people, which I just don’t buy. It doesn’t even make him scarier because most of the time he’s being outrun by a starving human being.

The only thing I liked about this movie in earnest was the soundtrack. The incidental Afrobeat songs they chose to play over the scenes of civilization are excellent, and composer John Frizzell uses one theme with a cello a few times that I liked so much that I spent a good deal of time tracking it down. Other than that, I can’t really recommend this. You know why? Cause someone made a much less ambitious croc film at exactly the same time and it’s ten thousand times better.

The only thing I liked about this movie in earnest was the soundtrack. The incidental Afrobeat songs they chose to play over the scenes of civilization are excellent, and composer John Frizzell uses one theme with a cello a few times that I liked so much that I spent a good deal of time tracking it down. Other than that, I can’t really recommend this. You know why? Cause someone made a much less ambitious croc film at exactly the same time and it’s ten thousand times better.Rogue

by Greg Maclean

Classification: Crocofrightenae Finallydecentus

Well it looks the universe has played another joke on a talented filmmaker. Like Tobe Hooper before him, director Greg Maclean had just made a really excellent horror film about a dismembering psychopath (Wolf Creek, which shares a few parallels with Texas Chainsaw, not the least of which is the fact that it’s really good) and the first offer that he took after its success was a crocodile film. It's short on cash, way less ambitious than all of it's predessecors, and you know what else? It’s the best damn croc film anyone’s ever made, so take fucking that universe. What is it they say about saving the best for last?

Well it looks the universe has played another joke on a talented filmmaker. Like Tobe Hooper before him, director Greg Maclean had just made a really excellent horror film about a dismembering psychopath (Wolf Creek, which shares a few parallels with Texas Chainsaw, not the least of which is the fact that it’s really good) and the first offer that he took after its success was a crocodile film. It's short on cash, way less ambitious than all of it's predessecors, and you know what else? It’s the best damn croc film anyone’s ever made, so take fucking that universe. What is it they say about saving the best for last?Rogue follows a group of people on a tour boat who answer a distress flare and have their boat capsized for their trouble. They wash up on a tidal island that will be gone by midnight and discover that they’re being stalked by a giant crocodile. It’s really simple, just enough money went into it and it’s pretty scary. I thought I was in trouble because the cinematography is as far from Wolf Creek’s overexposed grain as could be imagined, and the characters at first seem like one dimensional shitheads, but you know what? They change! People actually change over the course of a movie! Hallelujah there’s someone who knows how to write a script still alive out there! Maclean’s movie, like its crocodile, moves at an even pace and builds a lot of tension. Rogue also has one of the finer creature film conclusions I’ve yet seen. Making expert use of factual information, character-based tension, and an incredibly small space, Maclean manages to craft something pretty goddamn frightening with very little. I guess he figured out that what everyone else was doing wrong was trying to make their movie feel bigger than it is. Rogue feels small but it's successes are because it doesn't ever try to be more than it is. Primeval fails because it tries to seem big and important and it just doesn't have the budget for it. Maclean is honest and knows where his problems are and undercuts them with subtlety. In other words, he's a damn good director.

Radha Mitchell and Michael Vartan are our heroes and at no point does their relationship to one another seemed forced, unbelievable or hackneyed. They manage to make a really strong showing of themselves; I like Radha Mitchell, and she’s good in just about anything, despite the projects comparative awfulness, and her performance in Rogue is nice and even-handed. Michael Vartan does a really good job going from outsider dickweed to reluctant hero and Maclean makes us almost certain that this guy won’t be the hero for awhile with his thoughtfully written script. I like that a lot, when films play the changing protagonist game on you. It worked in Alien and Dawn of the Dead, and it works here. The Croc is good enough that I forgot I was watching an effect during the climax. Ignore the bad box art, watch Rogue. It’s the single greatest giant croc movie ever made and though I admit that isn’t saying a lot, Rogue is fun and harrowing; not quite as harrowing as Wolf Creek, mind you, but it’s still fun and you won’t leave quite as bummed out as you will from that film.

Radha Mitchell and Michael Vartan are our heroes and at no point does their relationship to one another seemed forced, unbelievable or hackneyed. They manage to make a really strong showing of themselves; I like Radha Mitchell, and she’s good in just about anything, despite the projects comparative awfulness, and her performance in Rogue is nice and even-handed. Michael Vartan does a really good job going from outsider dickweed to reluctant hero and Maclean makes us almost certain that this guy won’t be the hero for awhile with his thoughtfully written script. I like that a lot, when films play the changing protagonist game on you. It worked in Alien and Dawn of the Dead, and it works here. The Croc is good enough that I forgot I was watching an effect during the climax. Ignore the bad box art, watch Rogue. It’s the single greatest giant croc movie ever made and though I admit that isn’t saying a lot, Rogue is fun and harrowing; not quite as harrowing as Wolf Creek, mind you, but it’s still fun and you won’t leave quite as bummed out as you will from that film. And that concludes our Holiday season's look into the order of Giant Crocodile cinema. Have you learned something? No? Neither have I. After all, I actually watched all these movies! I will say that having seen the dregs of the film world turn out to throw their own entry into this order, it’s especially nice to see that someone gave me the film I’d wished for since seeing those few seconds of Alligator during Terror in the Aisles. I have Greg Maclean to thank for allowing me to walk away from the croc genre altogether knowing that it has a fitting conclusion. Does this mean no one’s going to make another gator film? HELL NO! I just know I can stop watching them.

And that concludes our Holiday season's look into the order of Giant Crocodile cinema. Have you learned something? No? Neither have I. After all, I actually watched all these movies! I will say that having seen the dregs of the film world turn out to throw their own entry into this order, it’s especially nice to see that someone gave me the film I’d wished for since seeing those few seconds of Alligator during Terror in the Aisles. I have Greg Maclean to thank for allowing me to walk away from the croc genre altogether knowing that it has a fitting conclusion. Does this mean no one’s going to make another gator film? HELL NO! I just know I can stop watching them.